OVENBIRDS

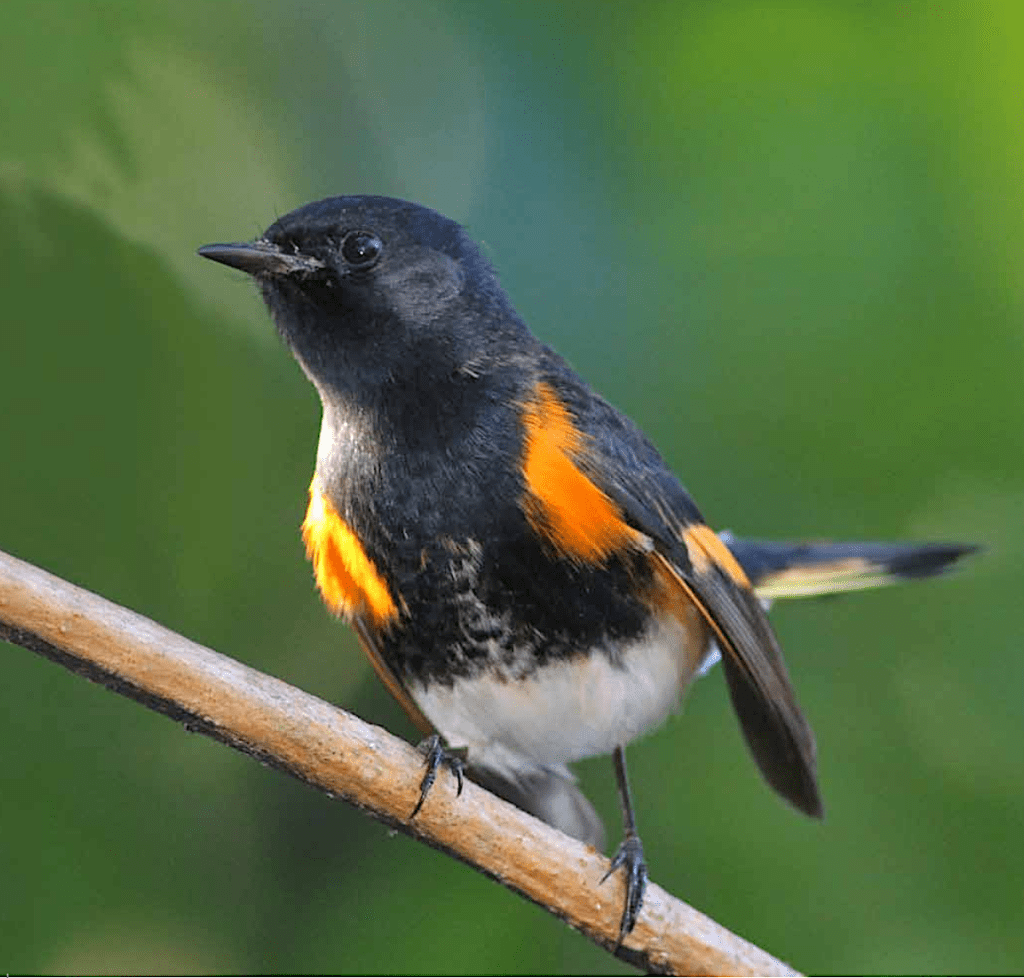

The Ovenbird Seiurus aurocapilla is a small winter-resident warbler with distinctive orange head feathers that can be raised into a crest. This accomplishment is mainly used in the breeding season as a way to impress and attract a mate, and maybe at other times if they are alarmed.

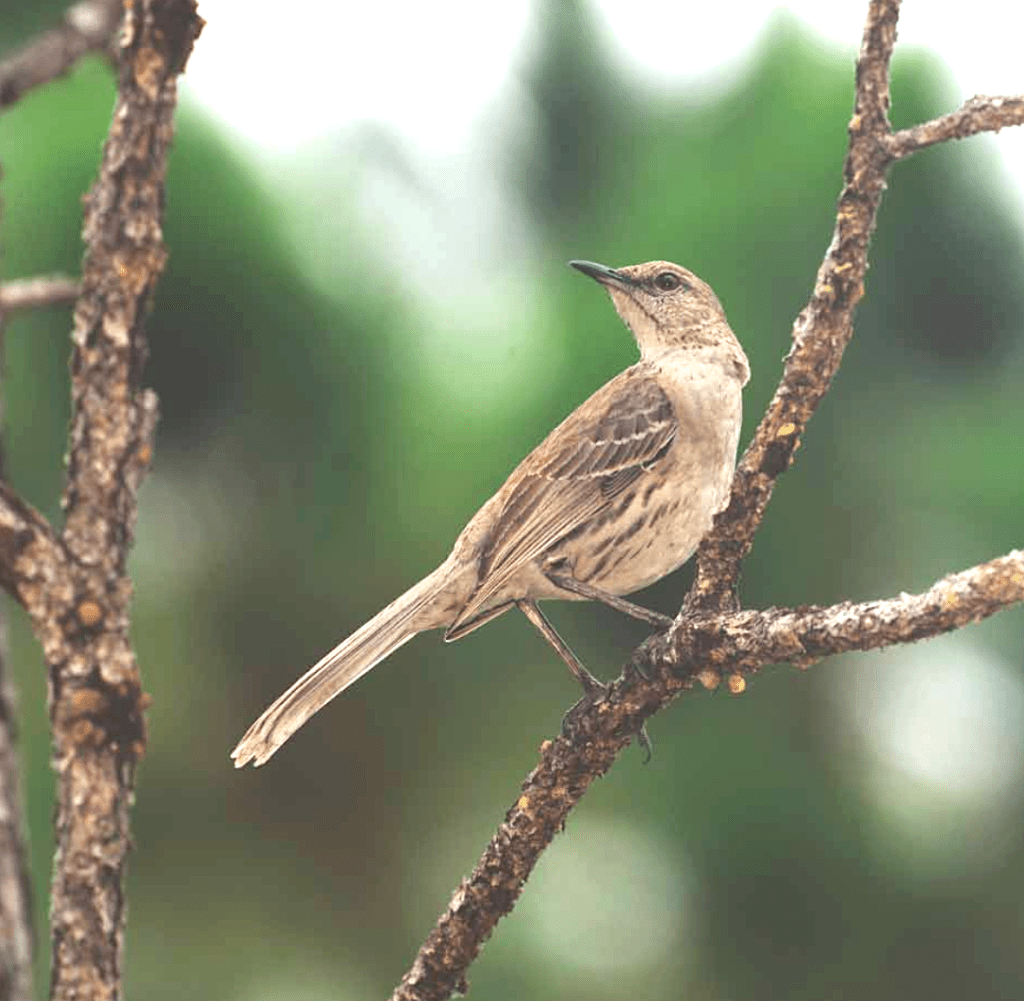

These are shy little birds and you may hardly be aware of them. They stay close to the ground and as they rootle their way through dead leaves and under shrubs, they look quite drab. See one lit up by the morning sun, however, and you’ll see how pretty and richly marked they are, with a smart orange head-stripe.

The Ovenbird – first classified by Linnaeus in 1766 – enjoys the taxonomic distinction of being the only bird of its genus in the warbler family Parulidae. It is a so-called ‘monotypic’ species. It was formerly lumped in with Waterthrushes and Parulas, but was fairly recently found to be genetically dissimilar and so the classifications were revised.

The ovenbird is so named because it builds a domed nest (‘oven’) with a side-entrance, constructed from foliage and vegetation. They tend to nest on the ground, making them vulnerable to predation. The species name for the ovenbird, Seiurus aurocapilla, has nothing to do with the nest shape, though. It derives from both Greek (Seiurus = wag-tail) and Latin aurocapilla = gold-capped). No, nothing to do with the lovely Taylor Swift either. Leave it.

Examples of the ‘chipping’ call and the song are below

Gauge the size of the bird against the pod it is standing on…

Credits: Tom Sheley, Woody Bracey, Charmaine Albury, Bruce Hallett, Gerlinde Taurer, Cephas / Wiki

Weird blue tint due to radical colour correction for the bad red algal bloom on the pond

Weird blue tint due to radical colour correction for the bad red algal bloom on the pond

You must be logged in to post a comment.