ANTILLEAN NIGHTHAWKS

Some years ago we went ‘backcountry birding’ for Birds of Abaco with photographer Tom Sheley. We drove the truck through forest, then into (former) sugar cane territory, then into scrubland. Red-winged blackbirds were enthusiastic with their rusty gate-hinge calling. Soon after Tom had set up his tripod with its baffling and weighty apparatus, we were in the midst of dozens of nighthawks as they swooped and dived (dove?) while hawking for flies. “The birds were completely unperturbed by our presence, and from time to time would zoom past within inches of our heads, making a swooshing noise as they did so”. Thanks to Robin Helweg-Larsen for the reminder that males may also make a distinctive ‘booming’ noise as they dive. Nighthawks catch flying insects on the wing, and are capable of great speed and manoeuvrabilty in flight. They generally forage at dawn and dusk – or (more romantically) at night in a full moon.

Nighthawks catch flying insects on the wing, and are capable of great speed and manoeuvrabilty in flight. They generally forage at dawn and dusk – or (more romantically) at night in a full moon.

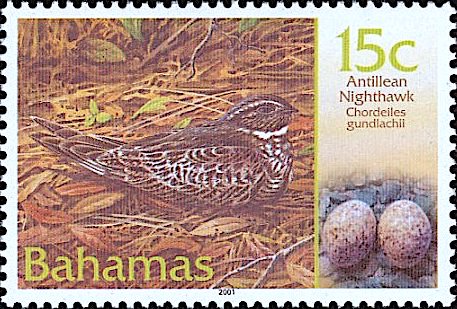

Besides aerial feeding displays, nighthawks may also be seen on the ground, where they nest. I say ‘nest’, but actually they hardy bother to make an actual nest, but just lay their eggs on bare ground. And, more riskily, this may well be out in the open rather than concealed. The eggs – usually 2 – hatch after 3 weeks or so, and after another 3 weeks the chicks fledge.

Besides aerial feeding displays, nighthawks may also be seen on the ground, where they nest. I say ‘nest’, but actually they hardy bother to make an actual nest, but just lay their eggs on bare ground. And, more riskily, this may well be out in the open rather than concealed. The eggs – usually 2 – hatch after 3 weeks or so, and after another 3 weeks the chicks fledge.

Fortunately their colouring enables them to blend in with the landscape – a good example of bird camouflage in natural surroundings.

Fortunately their colouring enables them to blend in with the landscape – a good example of bird camouflage in natural surroundings.

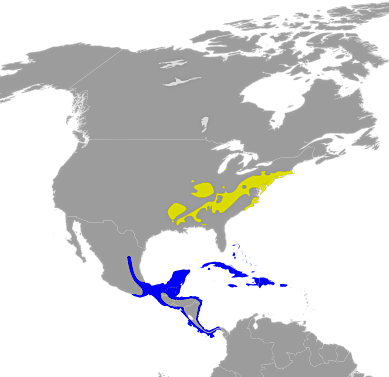

Antillean Nighthawk Chordeiles gundlachii, is a species of nightjar. These birds have local names such as ‘killa-ka-dick’, ‘pi-di-mi-dix’, ‘pity-pat-pit’, or variations on the theme, presumably onomatopoeic. Pikadik-(dik) will do for me. See what you reckon from these recordings (excuse the thick-billed vireo – I think – in the background):

Andrew Spencer / Xeno-Canto

Antillean Nighthawk Chordeiles gundlachii, is a species of nightjar. These birds have local names such as ‘killa-ka-dick’, ‘pi-di-mi-dix’, ‘pity-pat-pit’, or variations on the theme, presumably onomatopoeic. Pikadik-(dik) will do for me. See what you reckon from these recordings (excuse the thick-billed vireo – I think – in the background):

Andrew Spencer / Xeno-Canto

❖

As so often, the Bahamas Philatelic Bureau leads the way with natural history stamps. The 15c Antillean Nighthawk above featured in a 2001 bird set. You can see dozens more very excellent Bahamas bird, butterfly, fish, flower and other wildlife stamps HERE. Find out about Juan Gundlach, Cuban Natural Historian (he of the Antillean Nighthawk and the Bahama Mockingbird for example) HERE

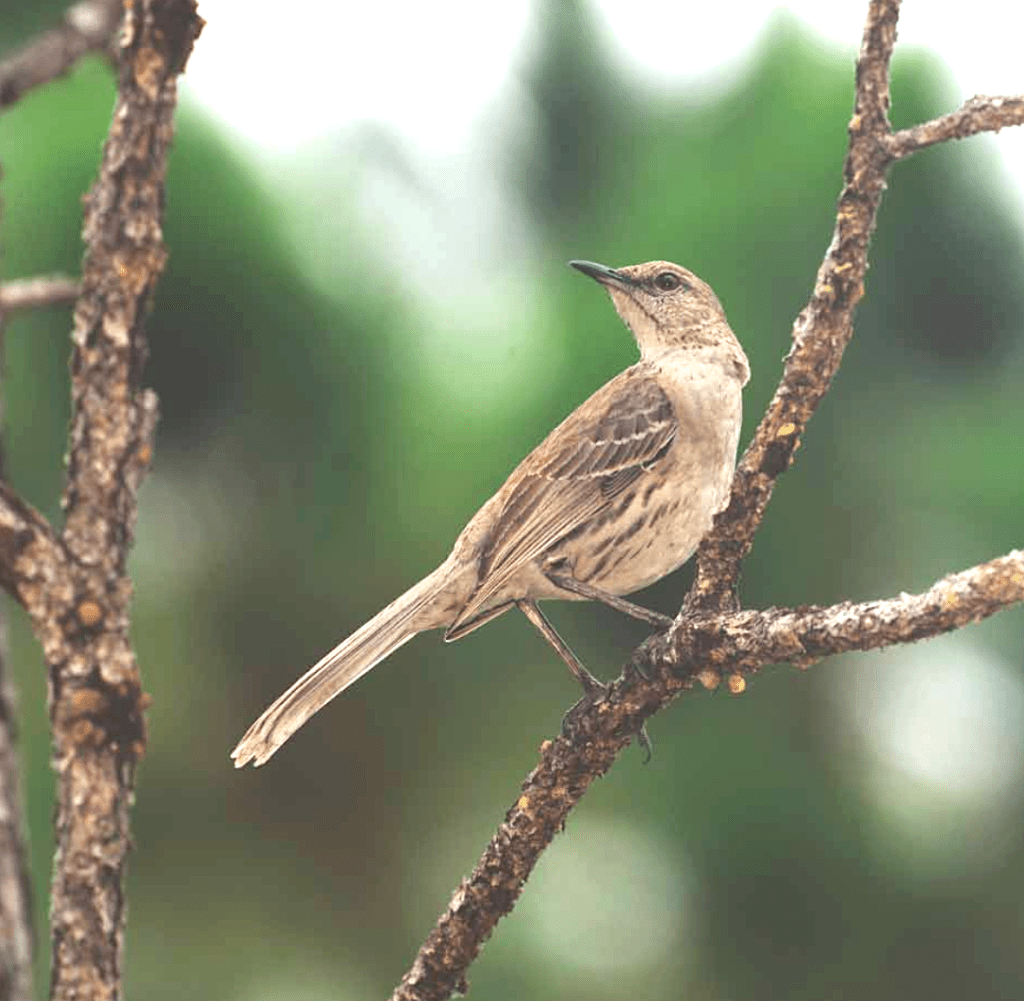

Find out about Juan Gundlach, Cuban Natural Historian (he of the Antillean Nighthawk and the Bahama Mockingbird for example) HERE

Credits: Sandy Walker (1); Stephen Connett (2, 3, 4, 5); Bruce Hallett (6); Andrew Spencer / Xeno-Canto (audio files); Audubon (7); Sibley / Audubon (8)

Credits: Sandy Walker (1); Stephen Connett (2, 3, 4, 5); Bruce Hallett (6); Andrew Spencer / Xeno-Canto (audio files); Audubon (7); Sibley / Audubon (8)

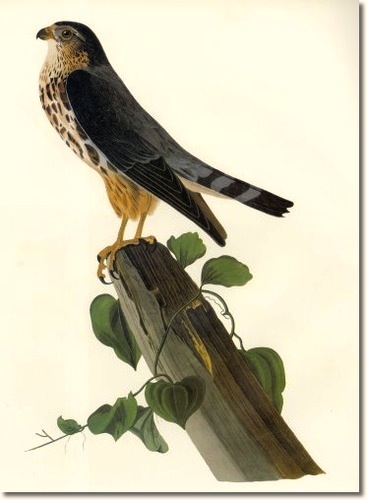

FIERCE LITTLE FALCONS: MERLINS ON ABACO

FIERCE LITTLE FALCONS: MERLINS ON ABACO

.

. .

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.