FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS: DECORATIVE CORAL-DWELLERS

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS Cyphoma gibbous are small marine gastropod molluscs related to cowries. The living animal is brightly coloured and strikingly patterned, but that colour only exists in the ‘live’ parts – the so-called ‘mantle’. The shell itself is usually pale, and characterised by a thick ridge round the middle. Whether alive or as shells, they are gratifyingly easy to identify. These snails live in the tropical waters of the Caribbean and the wider western Atlantic.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CORAL

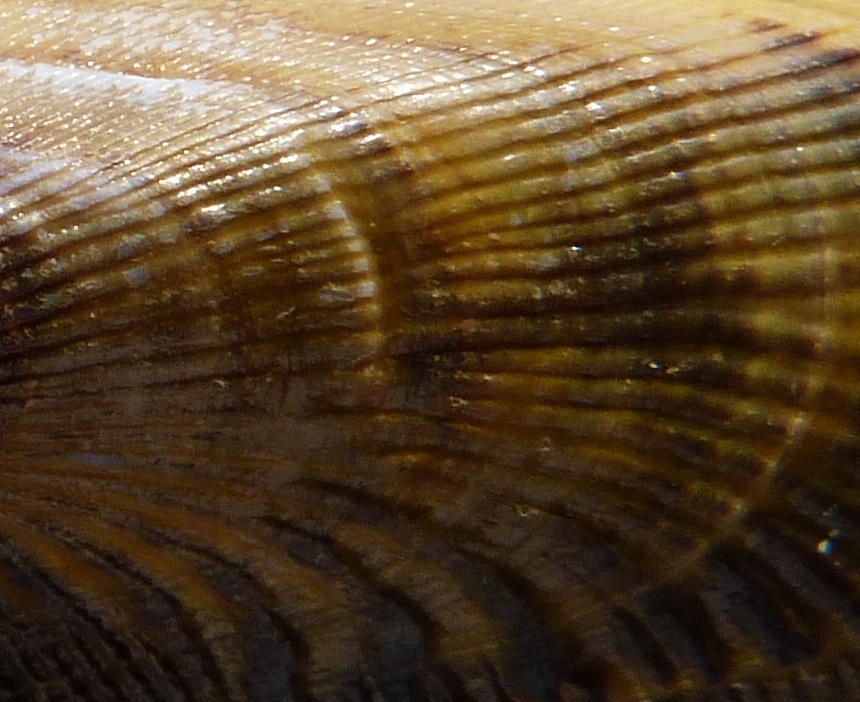

Flamingo tongue snails feed by browsing on soft corals. Often, they will leave tracks behind them on the coral stems as they forage (see image below). But corals are not only food – they provide the ideal sites for the creature’s breeding cycle.

Adult females attach eggs to coral which they have recently fed upon. About 10 days later, the larvae hatch. They eventually settle onto other gorgonian corals such as Sea Fans. Juveniles tend to live protectively on the underside of coral branches, while adults are far more visible and mobile. Where the snail leaves a feeding scar, the corals can regrow the polyps, and therefore the snail’s feeding preference is generally not harmful to the coral.

The principal purpose of the patterned mantle of tissue over the shell is to act as the creature’s breathing apparatus. The tissue absorbs oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. As it has been (unkindly?) described, the mantle is “basically their lungs, stretched out over their rather boring-looking shell”. There’s more to them than that!

THREATS AND DEFENCE

The species, once common, is becoming rarer. The natural predators include hogfish, pufferfish and spiny lobsters, though the spotted mantle provides some defence by being (a) startling in appearance and (b) on closer inspection by a predator, rather unpalatable. Gorgonian corals contain natural toxins, and instead of secreting these after feeding, the snail stores them. This supplements the defence provided by its APOSEMATIC COLORATION, the vivid colour and /or pattern warning sign to predators found in many animal species.

MANKIND’S CONTRIBUTION

It comes as little surprise to learn that man is considered to be the greatest menace to these little creatures, and the reason for their significant decline in numbers. The threat comes from snorkelers and divers who mistakenly / ignorantly think that the colour of the mantle is the actual shell of the animal, collect up a whole bunch from the reef, and in due course are left with… dead snails and their allegedly dull shells Don’t be a collector; be a protector…

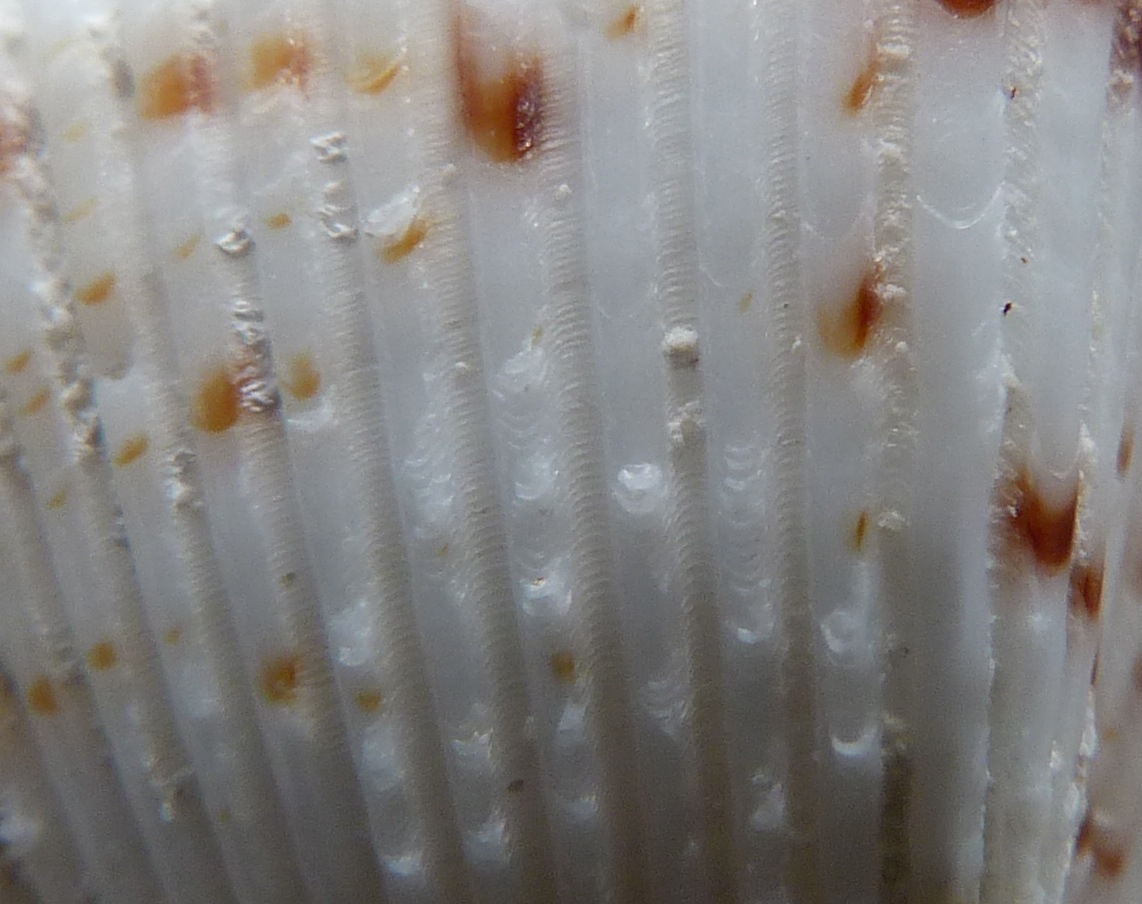

The photos below are of nude flamingo tongue shells. Until I read the ‘boring-looking shell’ comment, I believed everyone thought they were rather lovely… I did, anyway. I still do. You decide!

Image Credits: Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco; Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour; Wiki Leopard

![Cyphoma gibbosum shells [Cheers Wiki]](https://rollingharbour.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/220px-ovulidae_-_cyphoma_gibbosum.jpg)

![Cyphoma gibbosum (living) [cheers, Wiki]](https://rollingharbour.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/220px-cyphoma_gibbosum_living_21.jpg)

![Cyphoma gibbosum on Sea Fan [Cheers, Wiki]](https://rollingharbour.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/220px-cyphoma_gibbosum_0011.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.