SHOREBIRDS WADERS & SEABIRDS: 30 WAYS TO DISTINGUISH THEM

Today, September 6th, is World Shorebirds Day. Every year I look forward to scrolling back through the archives of ‘Birds of Abaco‘ for the occasion. It reminds me of the wonderful and plentiful varieties of birds that lead semi-aquatic or aquatic lives on and around the shores of Abaco. Some are permanent, others are migratory visitors.

.They can be broadly categorised as shorebirds, wading birds, and seabirds. With some bird species there may be doubt as to which category applies. In different parts of the world, the categories themselves may be named differently.

There is the strict Linnaean ordering of course, but in practice there is a degree of informal category overlap and some variation in the various bird guides. This is especially so between shorebirds and the smaller wading birds. Shorebirds may wade, and wading birds may be found on shores. Even if you have no problem distinguishing birds in the 3 categories, there are avian characteristics within each list that are interesting observations in themselves.

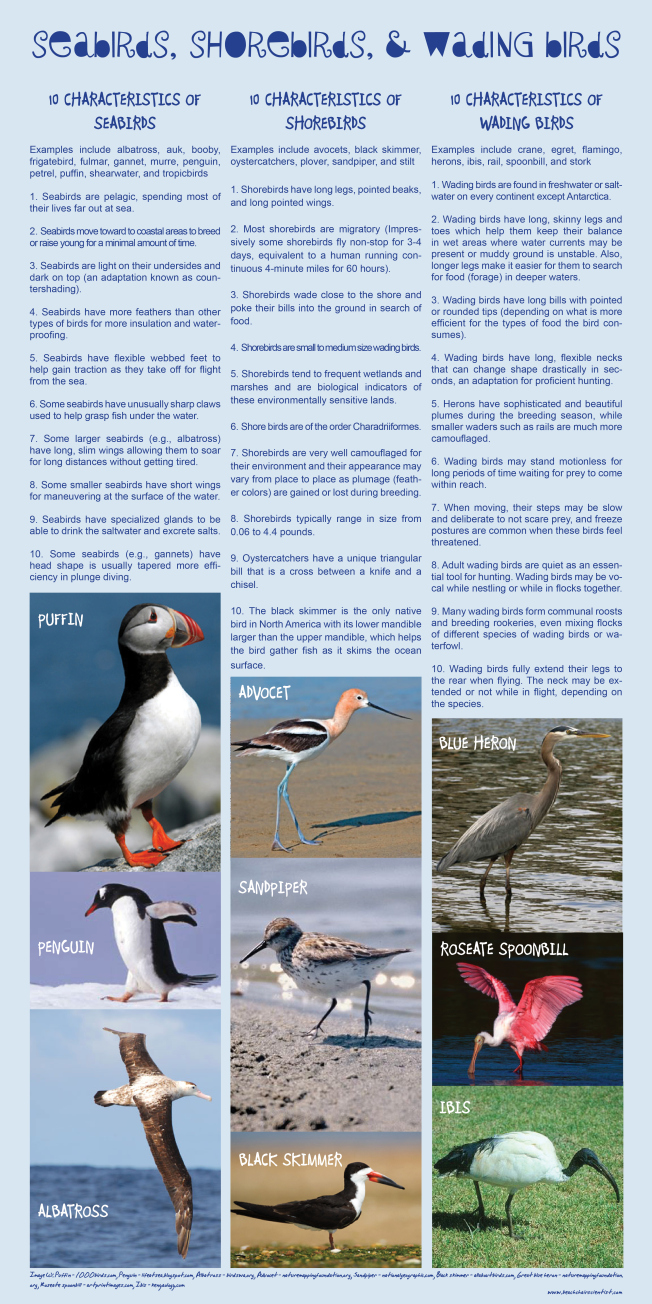

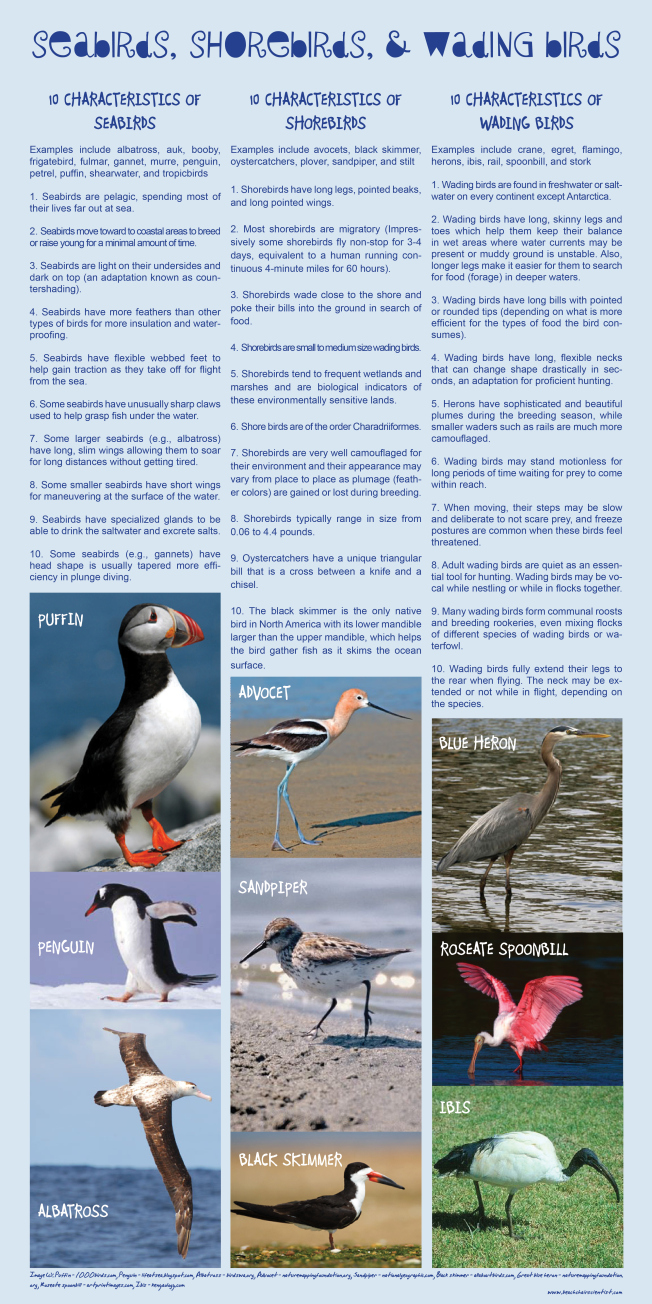

10 CHARACTERISTICS OF SHOREBIRDS

(Examples include avocet, black skimmer, oystercatcher, plover, sandpiper, and stilt)

1. Shorebirds have long legs, pointed beaks, and long pointed wings.

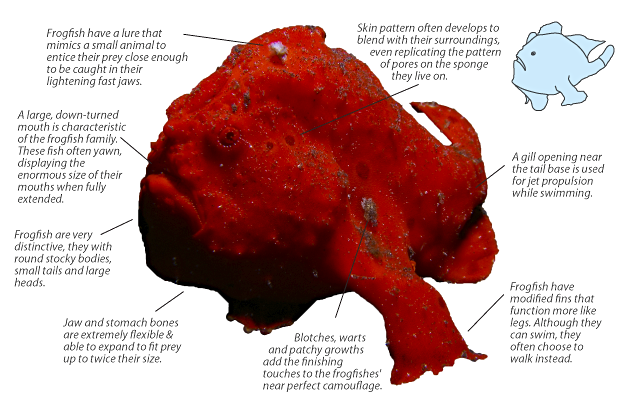

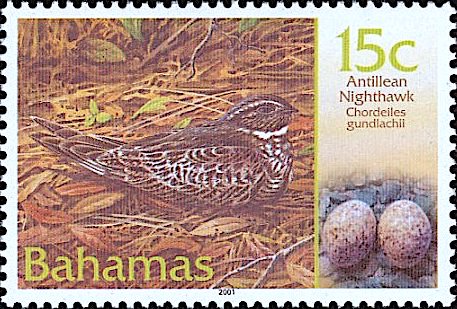

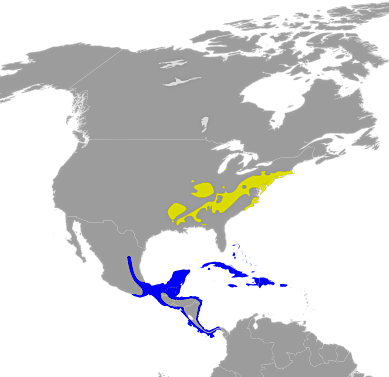

2. Most are migratory. Some shorebirds fly non-stop for 3-4 days to reach base.

3. Shorebirds are small to medium size birds. The shoreline is their main foraging ground.

4. They often feed close to the waterline and poke their bills into the ground in search of food.

5. Shorebirds also frequent wetlands and marshes and are biological indicators of these environmentally sensitive lands.

6. They are of the order Charadriiformes.

7. Shorebirds are very well camouflaged for their environment and their appearance may vary from place to place as plumage (feather colors) are gained or lost during breeding.

8. Shorebirds typically range in weight from 0.06 to 4.4 pounds.

9. Oystercatchers have a unique triangular bill that is a cross between a knife and a chisel.

10. The black skimmer is the only native bird in North America with its lower mandible larger than the upper mandible, which helps the bird gather fish as it skims the ocean surface.

10 CHARACTERISTICS OF WADING BIRDS

(Examples include crane, egret, flamingo, herons, ibis, rail, spoonbill, and stork)

1. Wading birds are found in freshwater or saltwater on every continent except Antarctica.

2. They have long, skinny legs and toes which help them keep their balance in wet areas where water currents may be present or muddy ground is unstable. Also, longer legs make it easier for them to search for food (forage) in deeper waters.

3. Wading birds have long bills with pointed or rounded tips (depending on what is more efficient for the types of food the bird consumes).

4. Wading birds have long, flexible necks that can change shape drastically in seconds, an adaptation for proficient hunting.

5. Herons have sophisticated and beautiful plumes during the breeding season, while smaller waders such as rails are much more camouflaged.

6. Wading birds may stand motionless for long periods of time waiting for prey to come within reach.

7. When moving, their steps may be slow and deliberate to not scare prey, and freeze postures are common when these birds feel threatened.

8. Adult wading birds are quiet as an essential tool for hunting. Wading birds may be vocal while nestling or while in flocks together.

9. Many wading birds form communal roosts and breeding rookeries, even mixing flocks of different species of wading birds or waterfowl.

10. Wading birds fully extend their legs to the rear when flying. The neck may be extended or not while in flight, depending on the species.

10 CHARACTERISTICS OF SEABIRDS

(Examples include albatross, auk, booby, frigatebird, fulmar, gannet, petrel, shearwater, and tropicbirds)

1. Seabirds are pelagic, spending most of their lives far out at sea.

2. Seabirds move toward to coastal areas to breed or raise young for a minimal amount of time.

3. Seabirds are light on their undersides and dark on top (an adaptation known as countershading).

4. Seabirds have more feathers than other types of birds for more insulation and waterproofing.

5. Seabirds have flexible webbed feet to help gain traction as they take off for flight from the sea.

6. Some seabirds have unusually sharp claws used to help grasp fish under the water.

7. Some larger seabirds (e.g. albatross) have long, slim wings allowing them to soar for long distances without getting tired.

8. Some smaller seabirds have short wings for maneuvering at the surface of the water.

9. Seabirds have specialised glands to be able to drink the saltwater and excrete salts.

10. Some seabirds (e.g. gannets) have a head shape that is usually tapered for more efficiency in plunge diving.

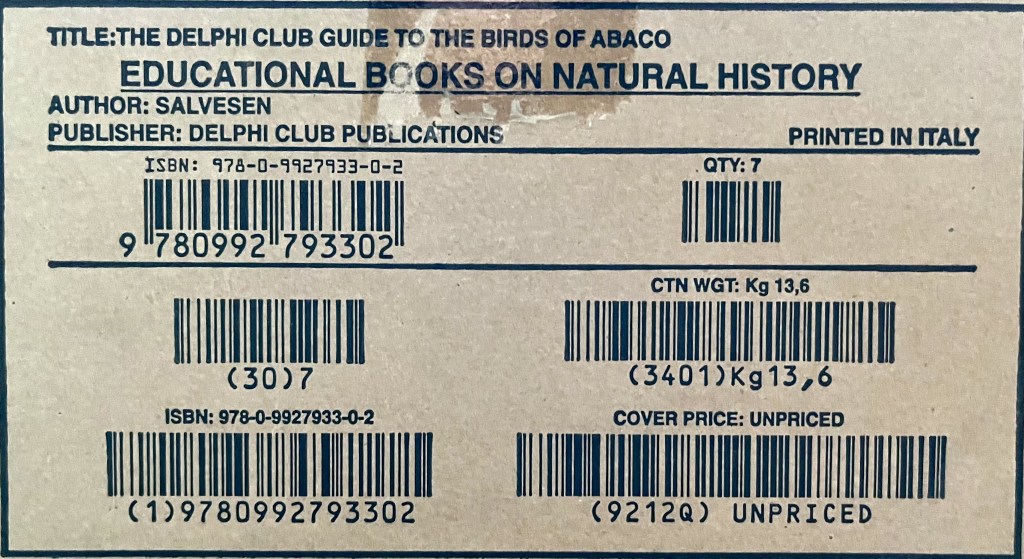

These lists were put together in useful chart form by the excellent Beach Chair Scientist

Table ©Beach Chair Scientist, with thanks for use permission;

Table ©Beach Chair Scientist, with thanks for use permission;

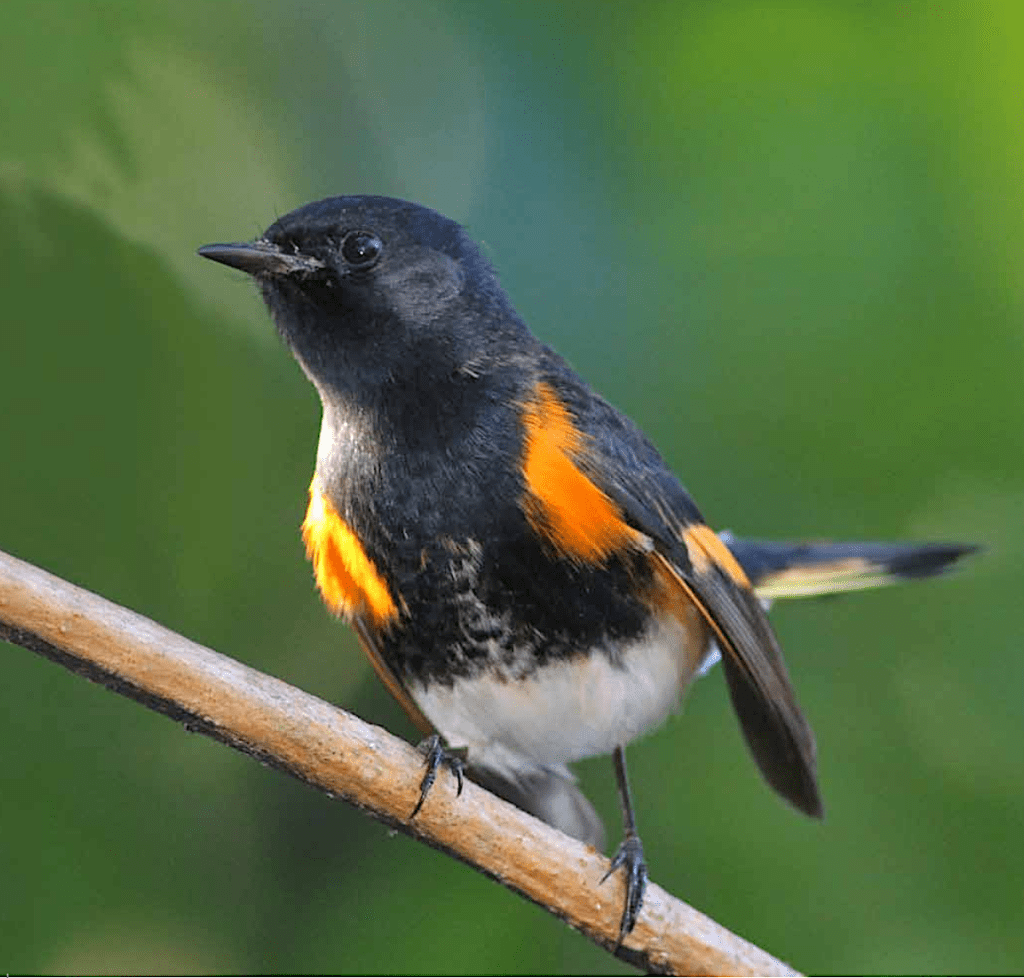

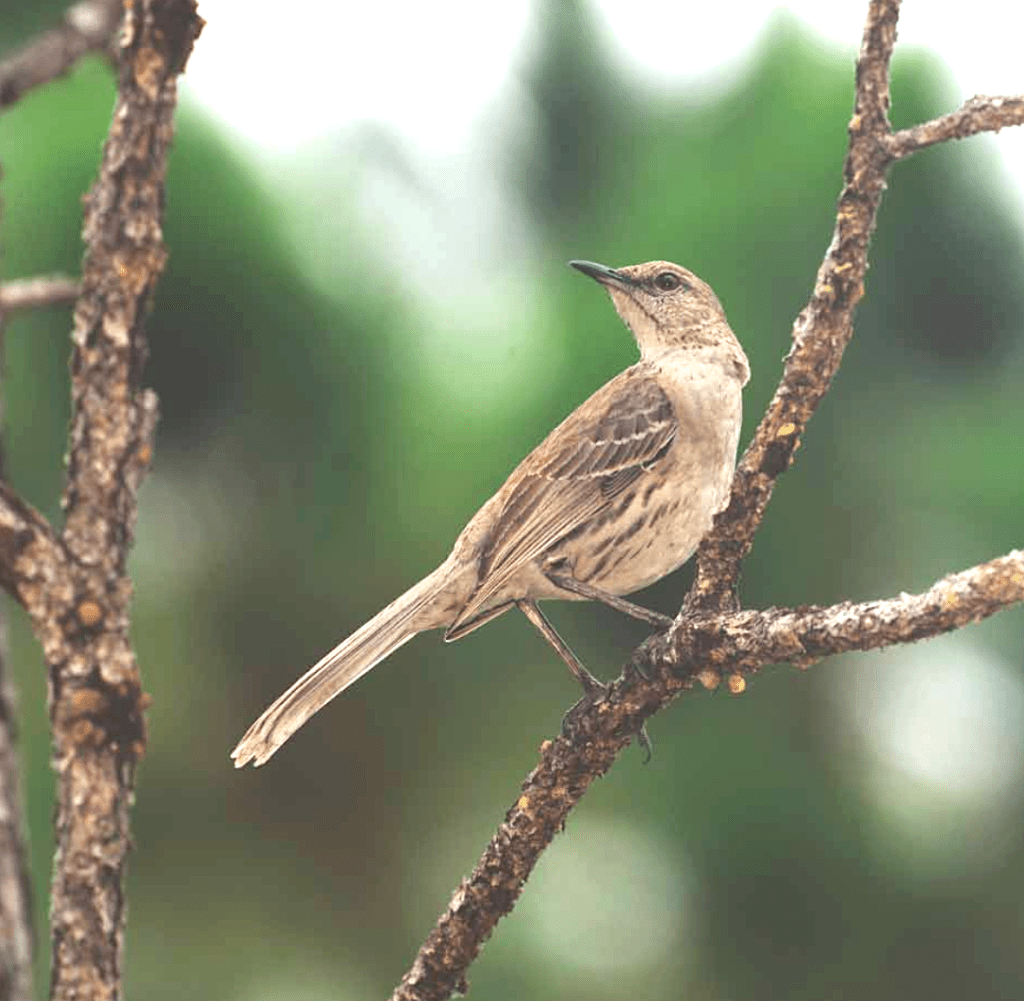

Image Credits: Keith Salvesen, Michael Vaughn, Tom Sheley

You must be logged in to post a comment.