WHEN NEW PROVIDENCE WAS OLD: MAPPING BAHAMAS HISTORY

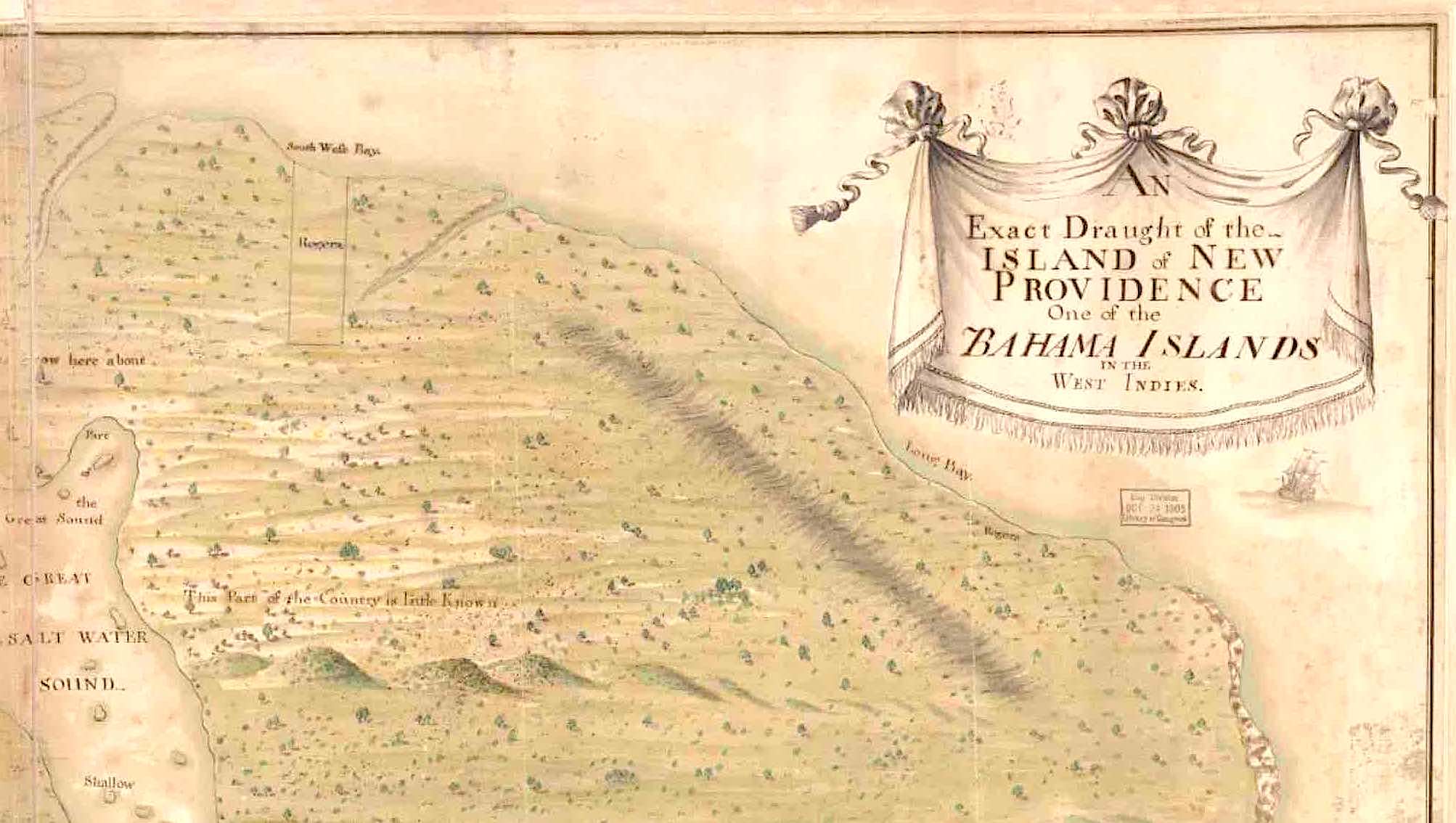

‘Exact Draught of the Island of New Providence

One of the Bahama Islands in the West Indies’

ORIENTATION

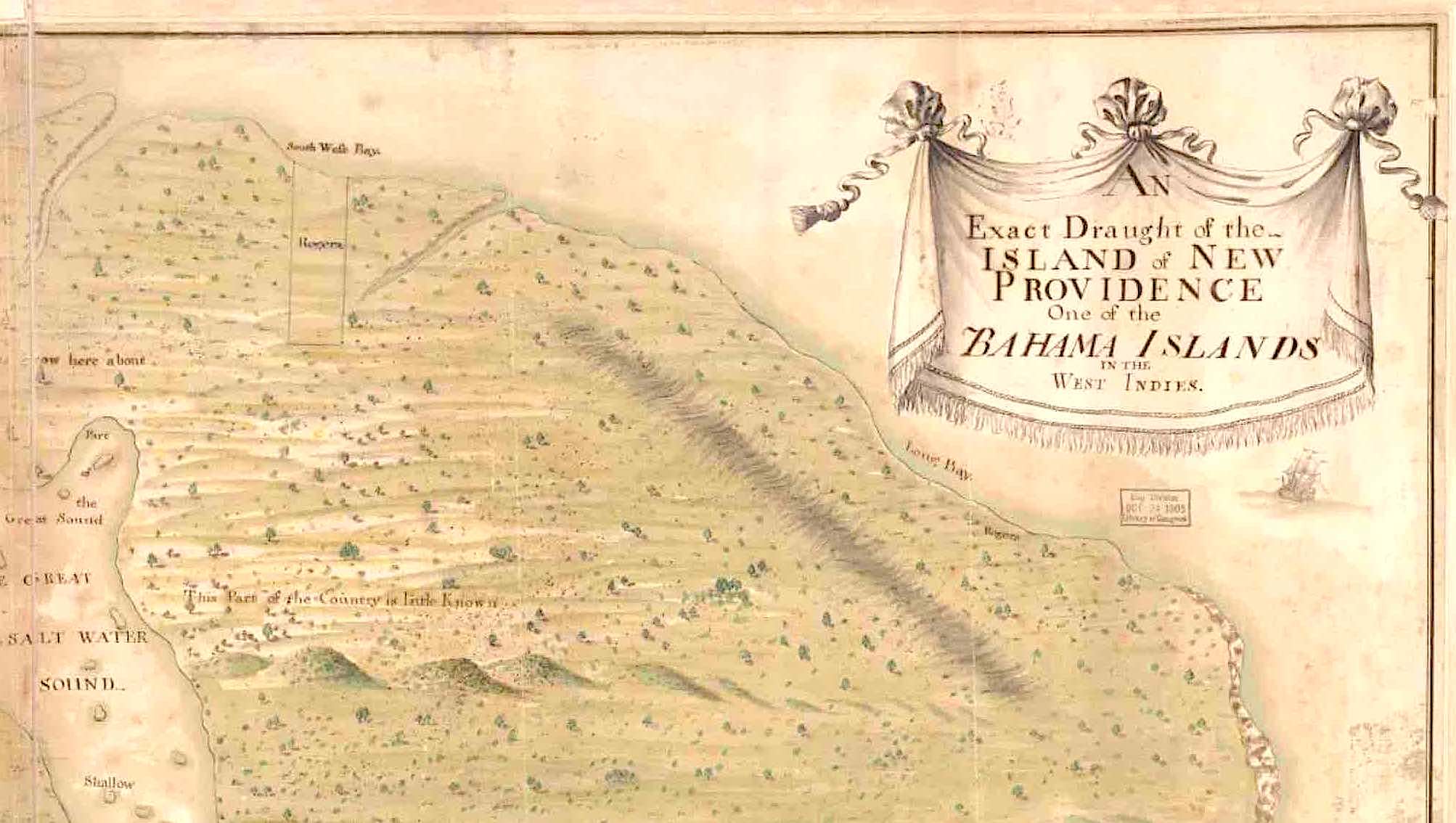

Lateral thinking is one thing; topsy-turvy thinking is in another league. The map that graces the top of this page is of New Providence and Nassau in the the early c18. By today’s exacting mapping conventions, which historically were less rigorously observed, it is upside-down, with Nassau on what we would call the south-west corner. However the convention that maps were orientated to the North was not generally accepted before C19. And in the middle ages maps were mostly orientated to the East (whence the term ‘orientating’). With advancing survey techniques from C17 on, maps were mostly orientated to the South like this map of New Providence.

DATE

The map is undated on the face of it, and I have found attributed dates of both 1700 and 1750 (see below). It could be anywhere in-between. At the time this map was made, New Providence was sparsely populated except for Nassau itself; and little was known about the island’s interior. Contemporary accounts describe a haven for pirates operating around the coastline. Not for nothing was Nassau protected by a battery and a fort. I’ve divided to map into sections to make it easier to take a closer look at each area. You can click each to enlarge.

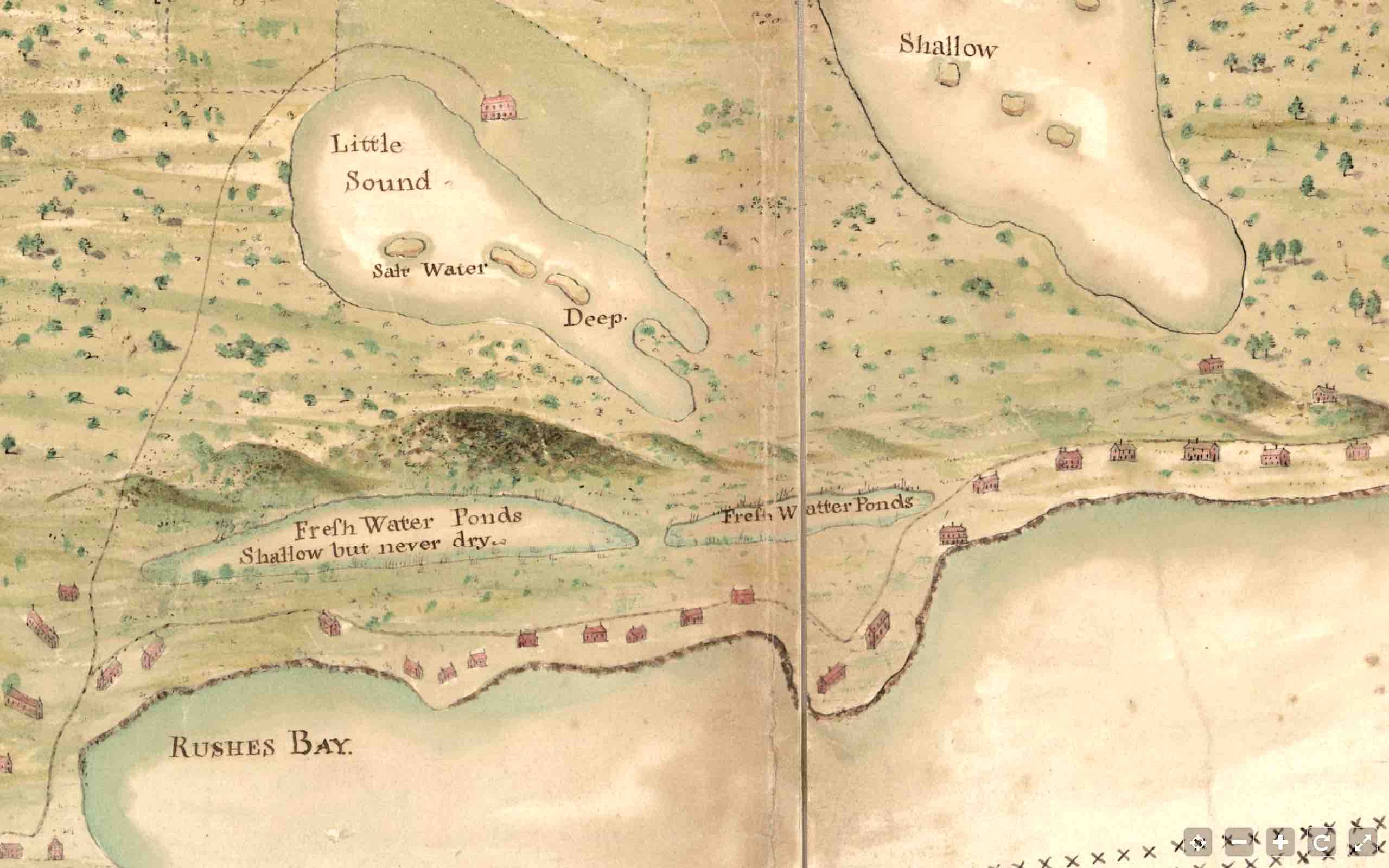

1. TOP LEFT CORNER (the south-east of NP in actuality), with the compass pointing downwards to the north. A smattering of houses dot the ‘west’ coast. There is one significant property above Little Sound, standing in what looks like a cleared or even cultivated area. I’ll look at that in more detail below. Note the words above The Great Salt Water Sound: “Very High Pines Grow Here Aboue (sic)”, evidence that forests of tall pines familiar even today on Abaco were found on NP 300 years ago. The island is otherwise mostly marked as if the landscape was fairly open.

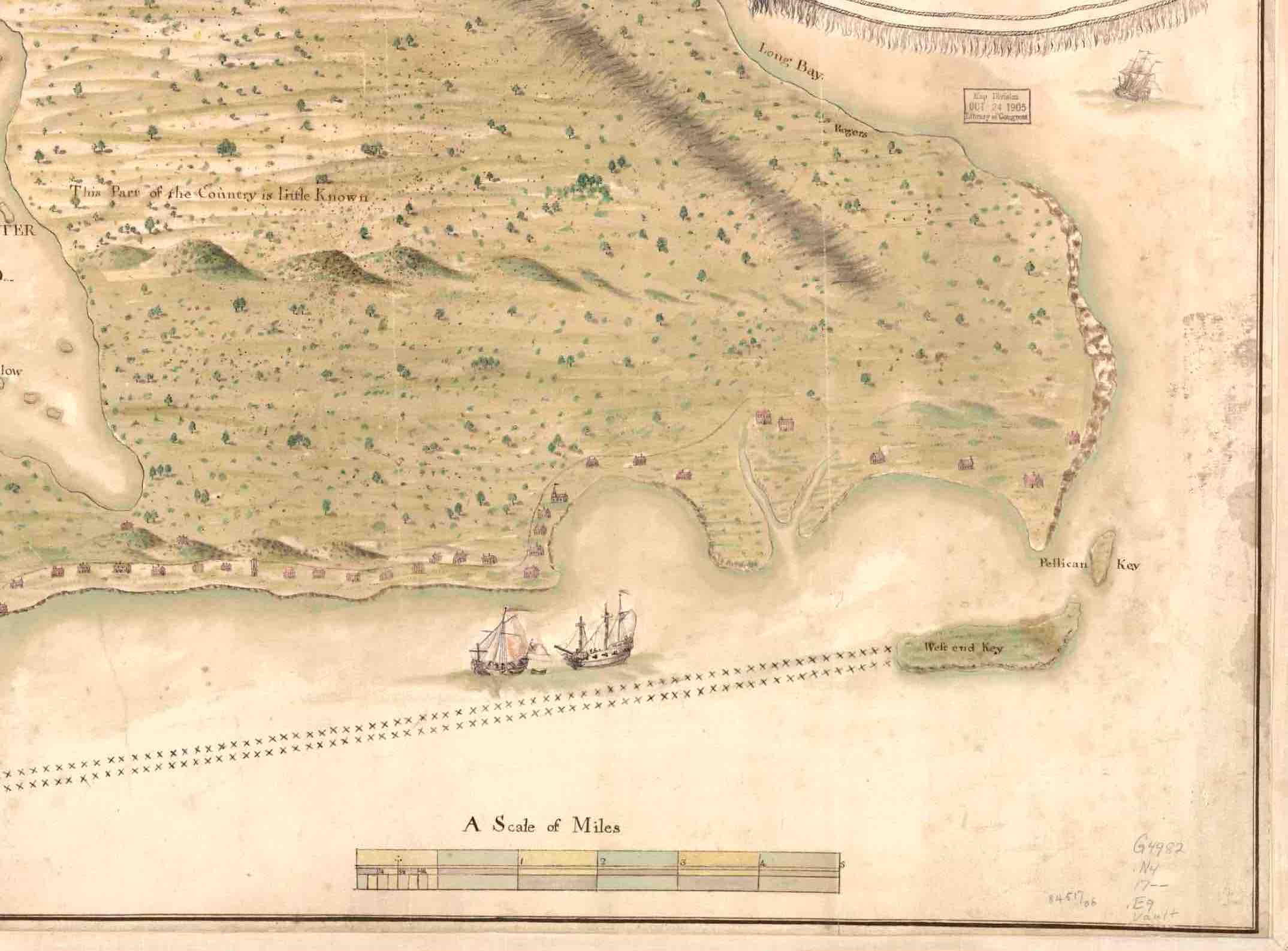

2. TOP RIGHT CORNER (south-west & west), with the confident title in a cartouche proclaiming exactness. This was not uncommon in historic map-making – the cartographical equivalent of today’s boastful product slogans – ‘simply the best’ and so on**. The caption next to the Great Sound, This Part of the Country is little Known, suggests an unexplored and perhaps hostile environment – possibly one of marshes and bogs. This sector of the island appears to have been uninhabited, or at least to having no population centres worth recording.

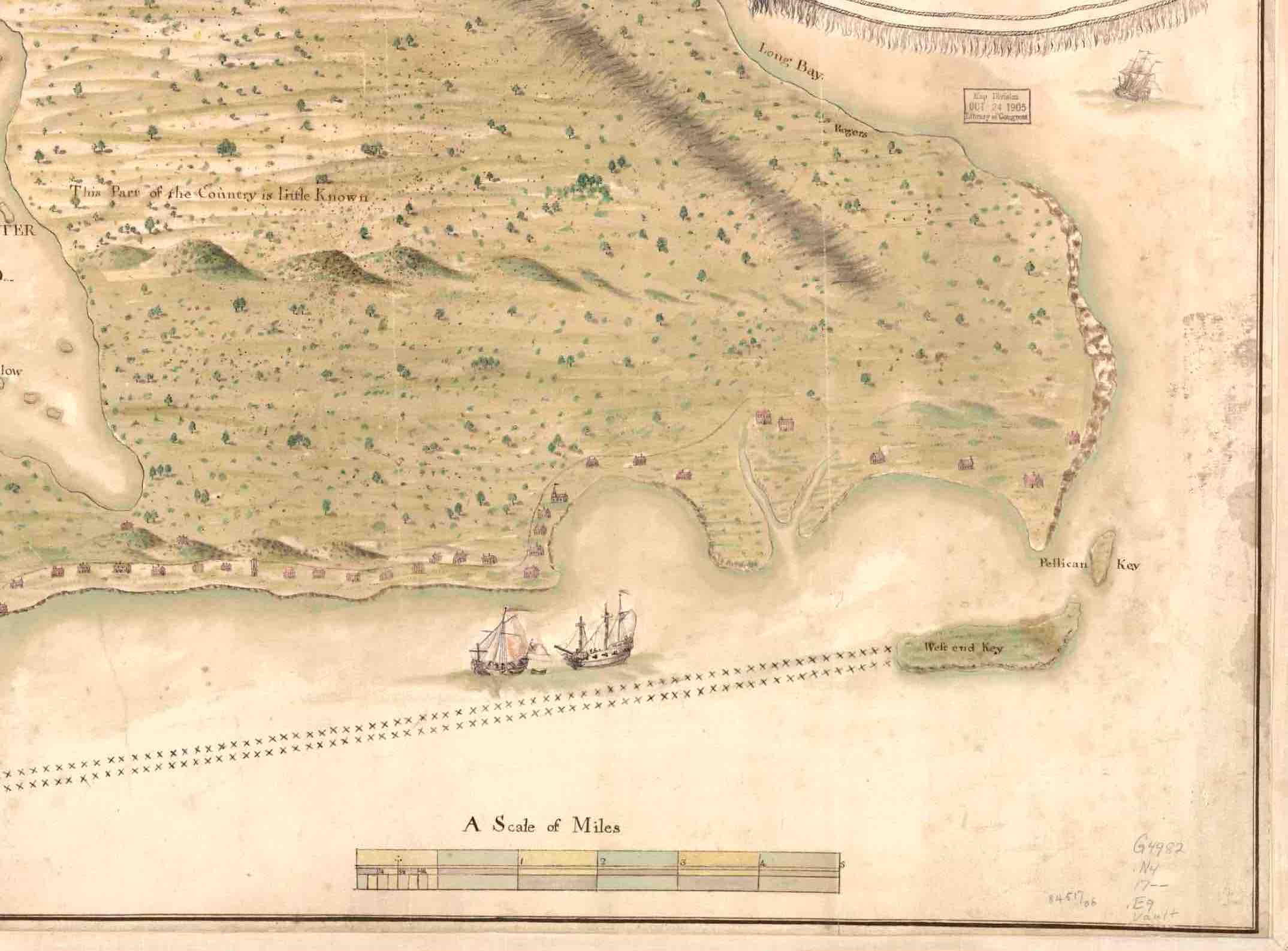

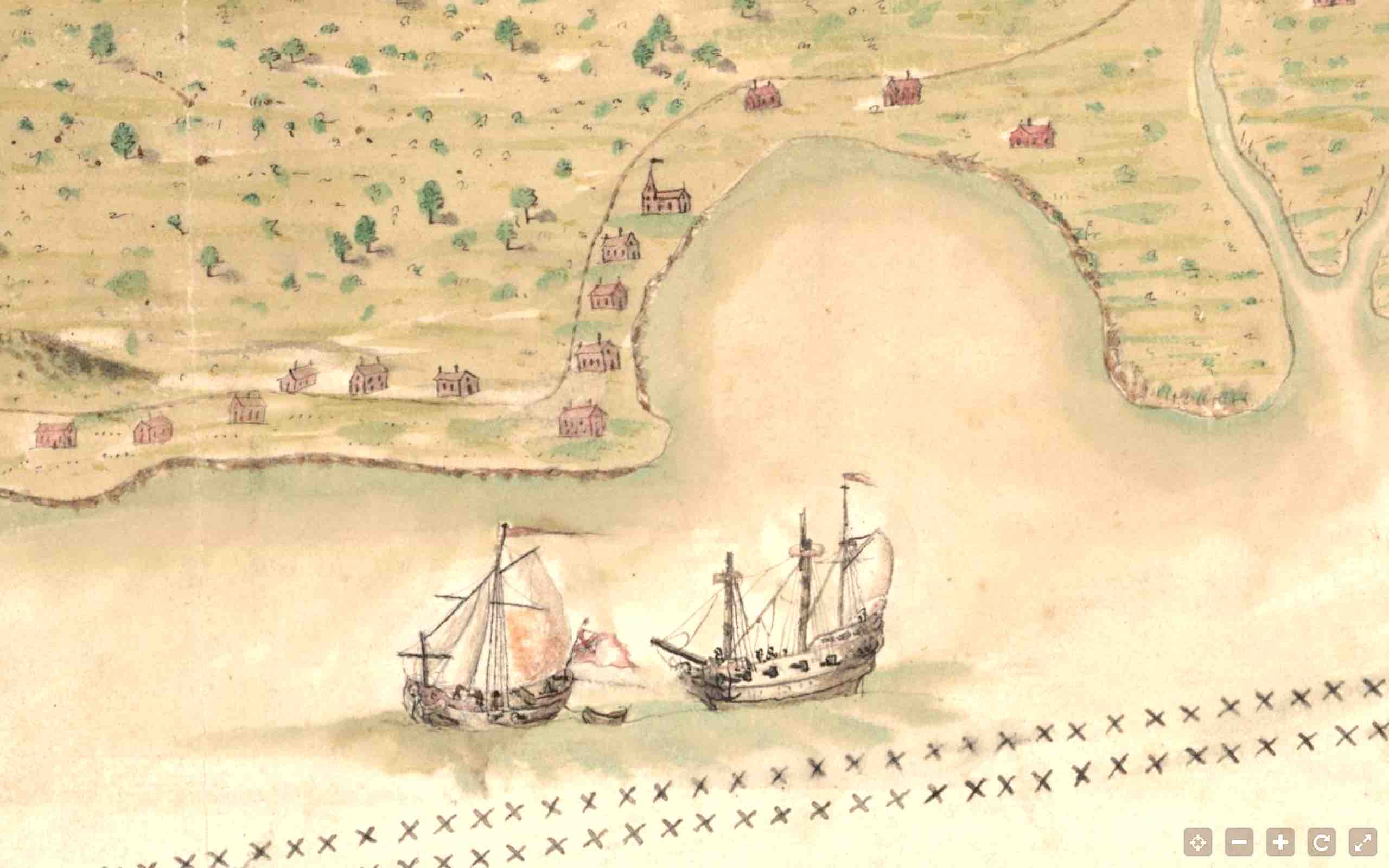

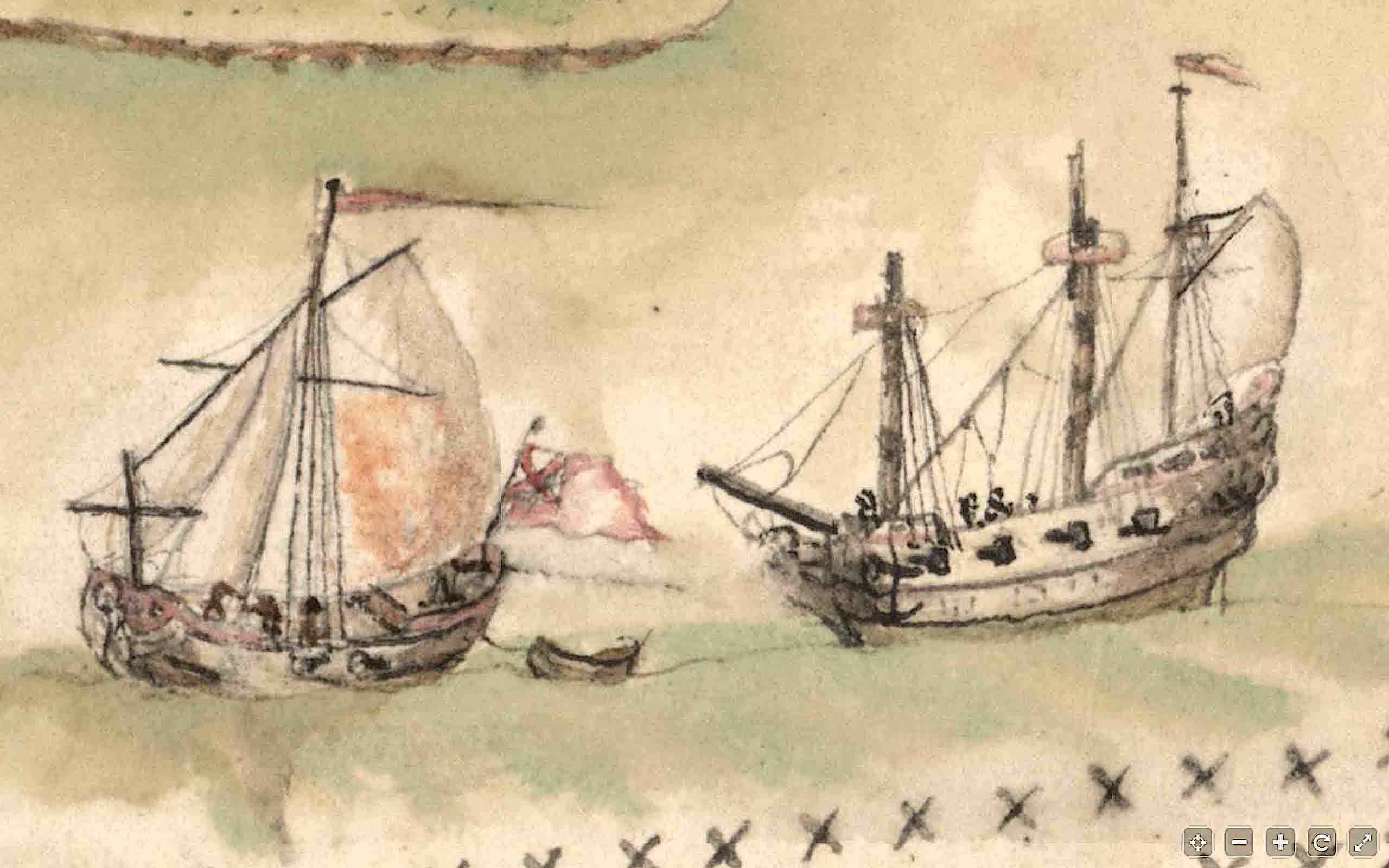

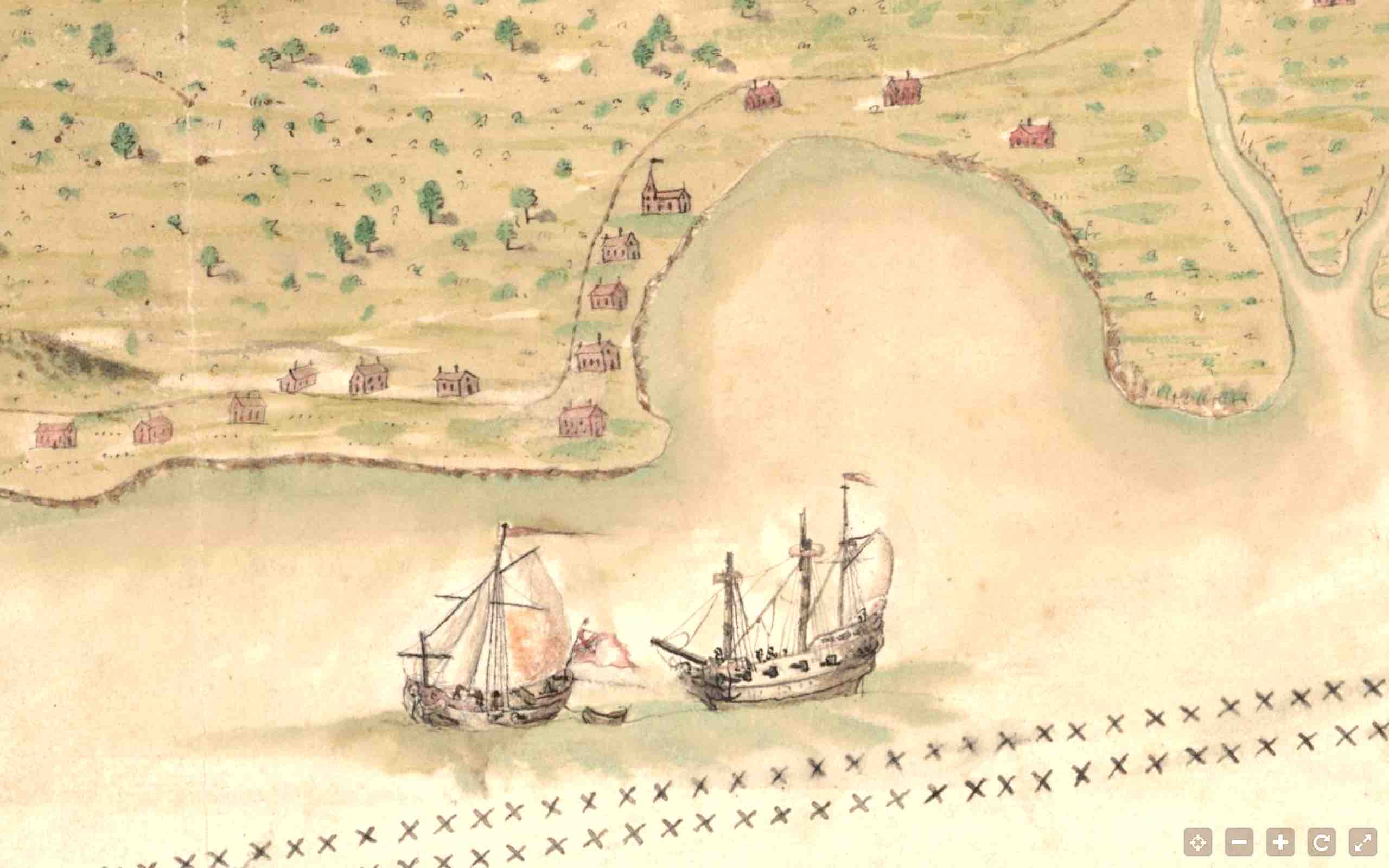

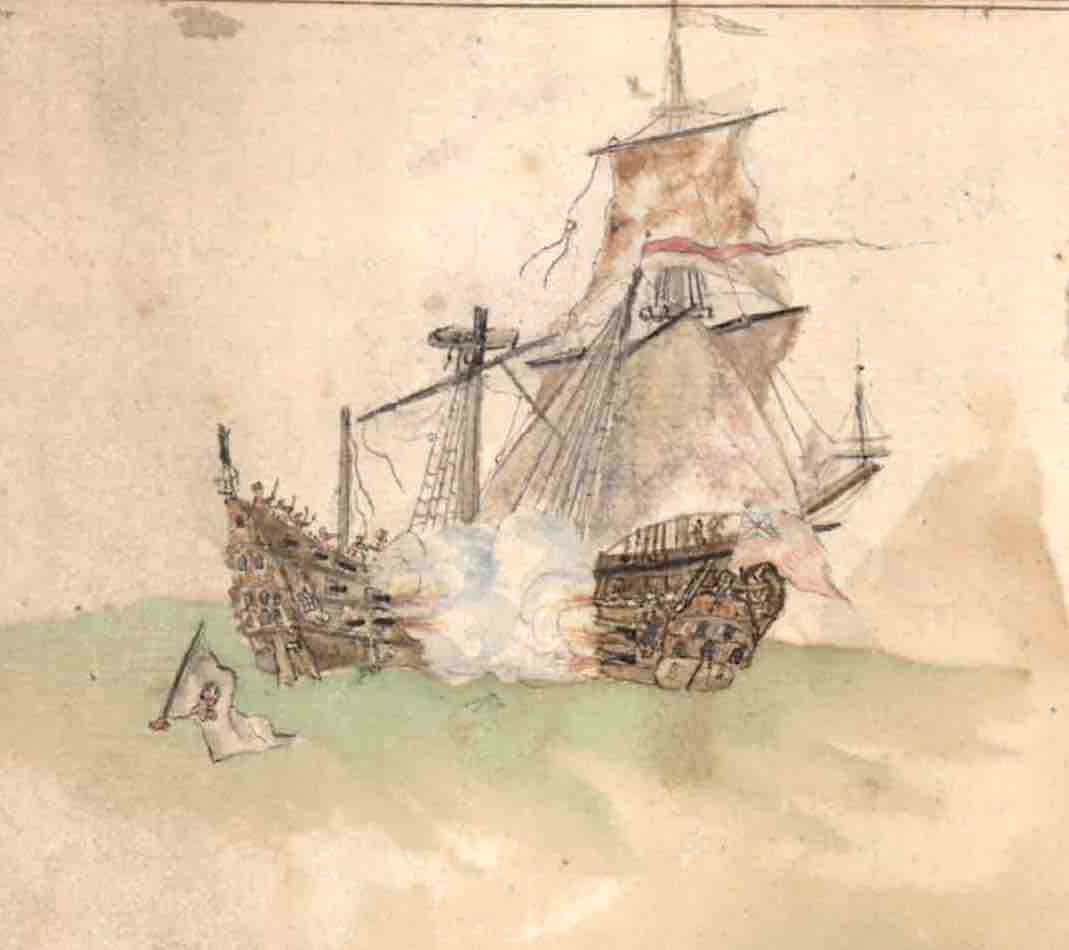

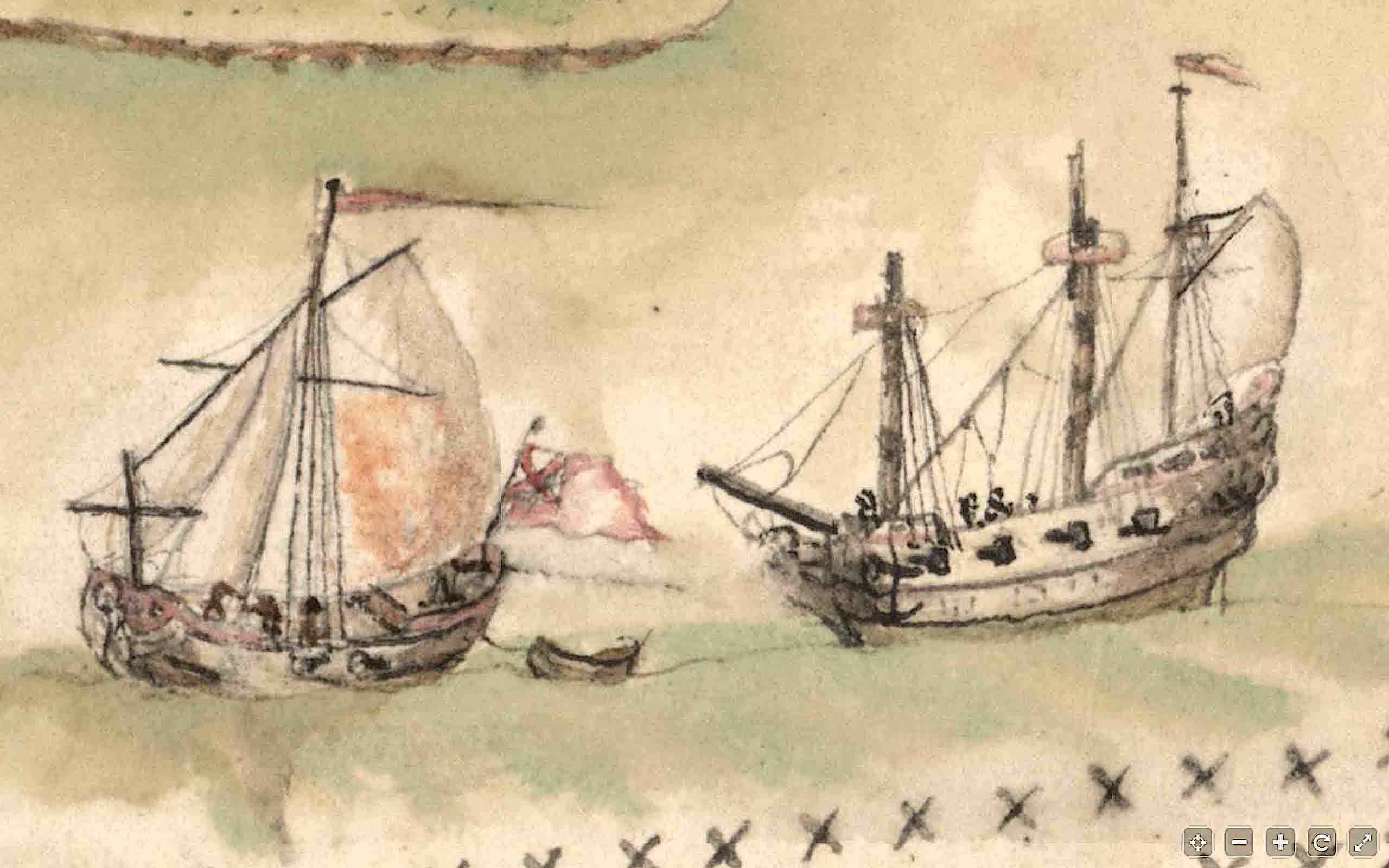

3. BOTTOM RIGHT CORNER (north-west). At last there is more evidence habitation, with a string of dwellings along the coastline. The 2 cays shown have names, West End and ‘Pellican’. And it looks as though the two ships have set out from port. On the left side of the bay above them, a church can be seen. Initially I thought the double row of crosses might indicate an area close to the shoreline that might be safe – or at least safer – from pirate attack. The leading ship – as the detailed crop shows clearly – is a warship. No harm in romantically speculating that it is escorting a trading vessel… More recently an online friend Klausbernd told me that the double crosses on map are in fact a navigational aid indicating cross bearings.

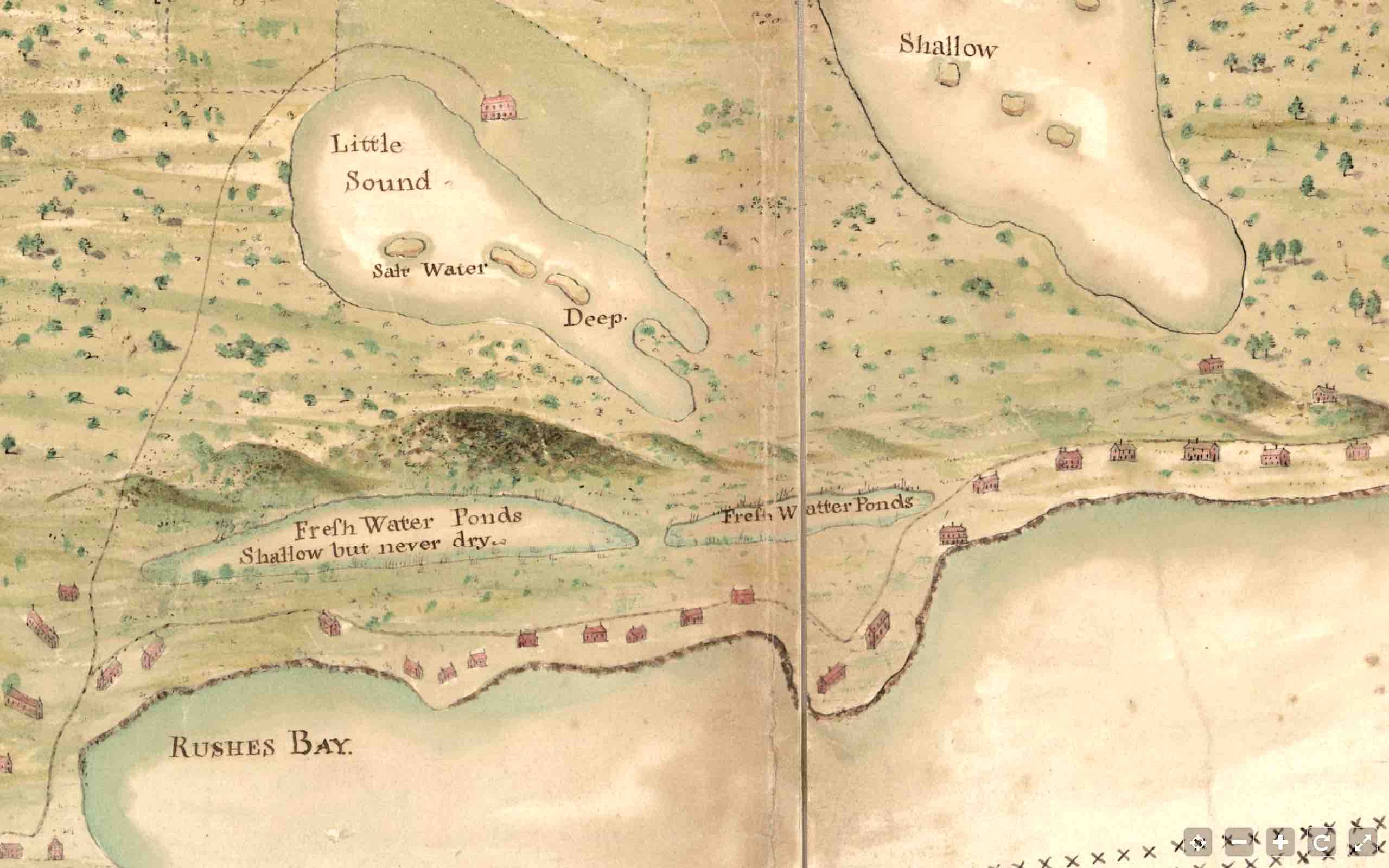

4. BOTTOM MIDDLE SECTION As we move towards the main – indeed only – town on the island, it is clear that the northern coast was the most desirable place to live. The scattering of houses along the coast continues; and the captions for the ponds show a possible reason why: fresh water, on an island where other areas of water are actually marked as ‘salt’ or which might have been unpleasantly brackish. And now we can see more of the posh establishment I referred to above. Not only did it lie in open (or perhaps cultivated) country, but it was plainly of some importance. It is notably larger that other buildings depicted, for a start; and it has its own very long track that forks off the coastal track.

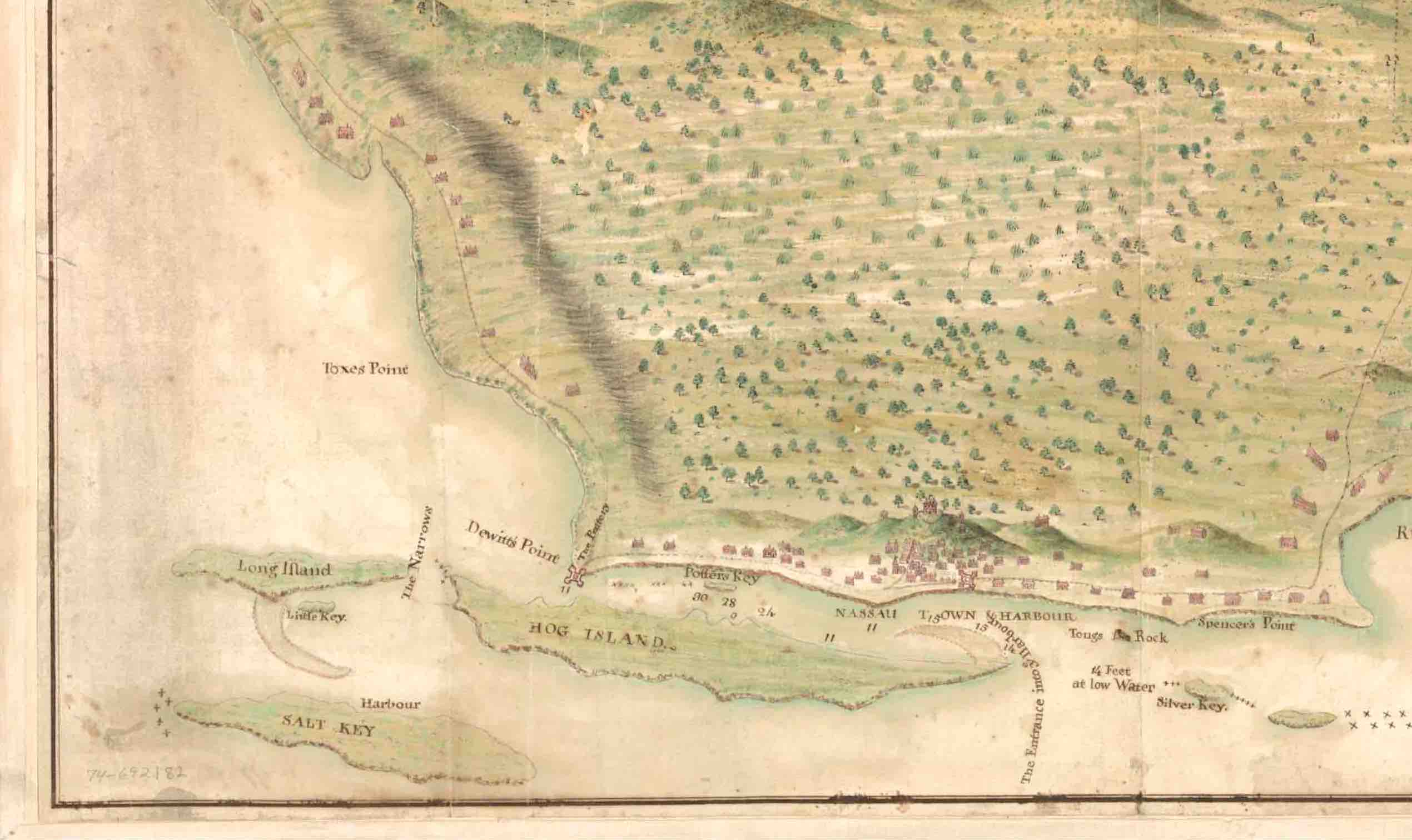

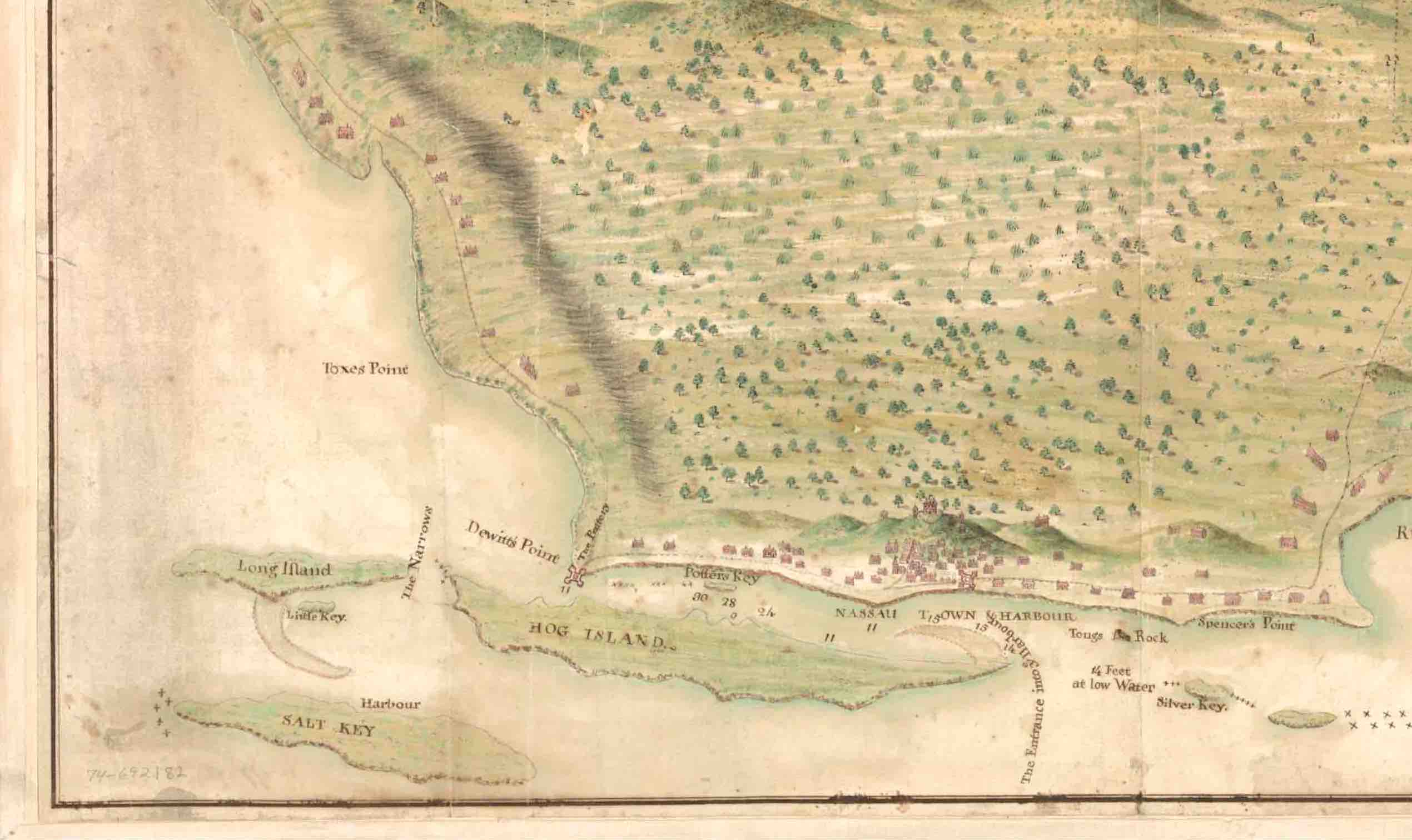

5. BOTTOM LEFT CORNER: NASSAU We have reached the big city, the centre of the population, and the port – with the harbour entrance handily marked. It bore the same name then as now; though the other names marked (as far as I can make out) have mostly if not all changed over 3 centuries. The Baha Mar development and its attendant travails seem light years away from this map. The double line of crosses ends here (bottom right at the first cay). If they marked a safe zone for vessels passing back and forth into Nassau harbour, they did not need to extend further because of the town fortifications (see detailed crop). There is a fort right on the shore; and at the far end of the harbour sound is a battery at Drewitt’s Point. The town is watched over by a substantial building – presumably a Governor’s residence – that is surrounded by a stockade . In the early c18 Nassau put on a show of strength to deter invaders and pirates.

DO WE KNOW THE EXACT DRAUGHT’S EXACT DATE?

The map itself is undated. The Library of Congress, whose map I have chopped up for this post, simply dates it as 17– and notes:

Manuscript, pen-and-ink and watercolor; Has watermark; Oriented with north to the bottom; Relief shown pictorially and by shading; Depths shown by soundings.

The excellent David Rumsey Historical Map Collection chooses the year 1750, the maker unknown. Another source puts the date at 1700.

Whichever, a clue to establish the map in the first half of the c18 is that the publisher is believed to be ‘William Innys [et al.]’, London. Innys and his brother John (the ‘et al’ presumably) were active at that time. In 1726, for example, they published an edition of Newton’s Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (first published in 1687), indicating that they must already have been well-established.

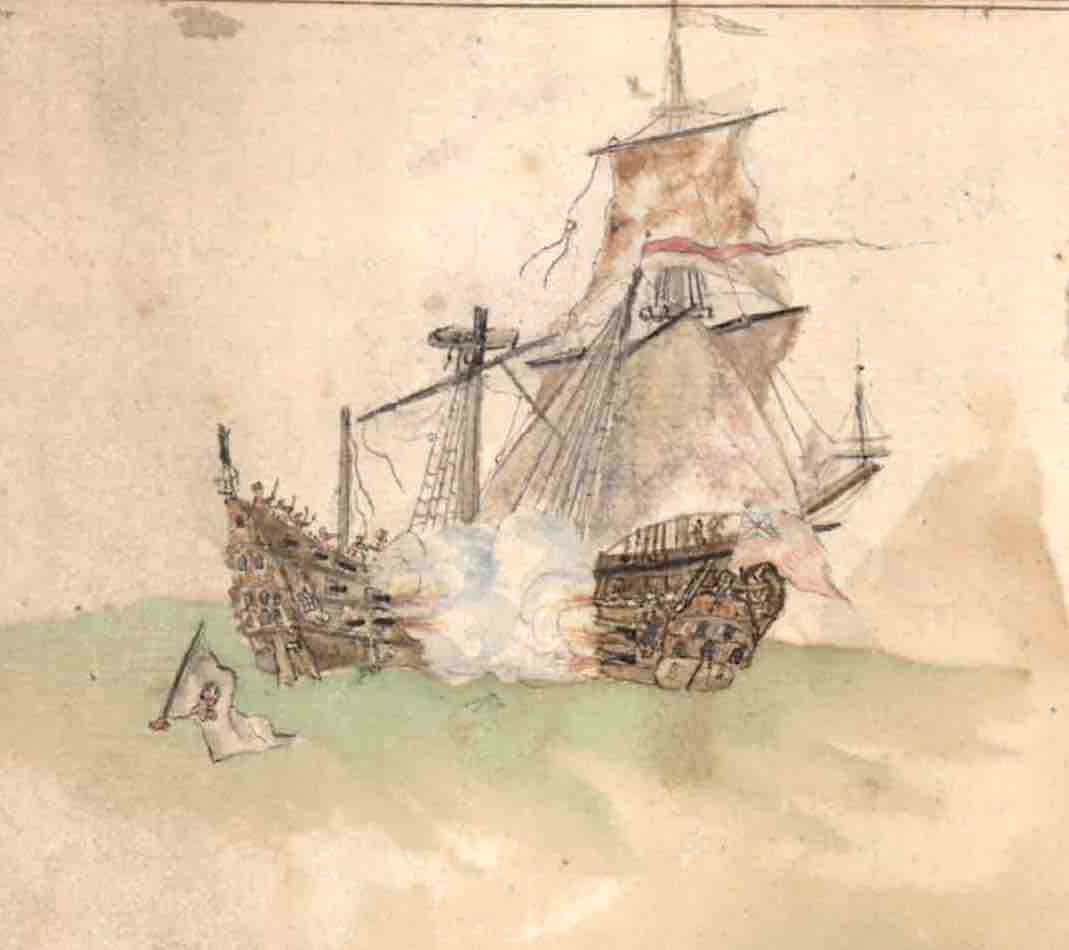

WHAT ABOUT THE PIRATES?

The “Deposition of Capt. Matthew Musson” made on 5 Jul 1717 in London, contains some excellent contemporary pirate-based material. The middle passage in particular gives an indication how well organised and extremely well-armed the pirates were. And it is clear that piracy was actually driving inhabitants away from New Providence.

- “On March last he was cast away on the Bahamas. At Harbour Island he found about 30 families, with severall pirates, which frequently are comeing and goeing to purchase provissons for the piratts vessells at Providence. There were there two ships of 90 tons which sold provissons to the said pirates, the sailors of which said they belong’d to Boston”.

- “At Habakoe one of the Bahamas he found Capt. Thomas Walker and others who had left Providence by reason of the rudeness of the pirates and settled there. They advis’d him that five pirates made ye harbour of Providence their place of rendevous vizt. [Benjamin] Horngold, a sloop with 10 guns and about 80 men; [Henry] Jennings, a sloop with 10 guns and 100 men; [Josiah(s)] Burgiss, a sloop with 8 guns and about 80 men; [Henry?] White, in a small vessell with 30 men and small armes; [Edward] Thatch, a sloop 6 gunns and about 70 men. All took and destroyd ships of all nations except Jennings who took no English; they had taken a Spanish ship of 32 gunns, which they kept in the harbour for a guardship”.

- “Ye greatest part of the inhabitants of Providence are. already gone into other adjacent islands to secure themselves from ye pirates, who frequently plunder them. Most of the ships and vessells taken by them they burn and destroy when brought into the harbour and oblidge the menn to take on with them. The inhabitants of those Isles are in a miserable condition at present, but were in great hopes that H.M. would be graciously pleas’d to take such measures, which would speedily enable them to return to Providence their former settlement, there are severall more pirates than he can now give an accot. of that are both to windward and to leward of Providence that may ere this be expected to rendevous there he being apprehensive that unless the Governmt. fortify this place the pirates will to protect themselves”. Signed, Mathew Musson. Endorsed, Read 5th July, 1717. 1½ pp. [C.O. 5, 1265. No. 73.]

CAN I BUY THIS MAP FOR MY WALL?

You certainly can. Well, not an original obviously. But you can find prints of it on eBay and elsewhere – just google the map title. You can get a modern copy for around $20 + shipping

** I have an enjoyable example of this tendency on a William Guthrie map of Europe dated c1800 that I own. A map from “the beft authorities” could surely have no serious rival!

Credits: Library of Congress Online Catalog (Geography and Map Division); David Rumsey Historical Map Collection; Baylus C Brooks, Professional Research & Maritime Historian, Author, & Conservator / “America and West Indies: July 1717, 1-15,” in Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 29, 1716-1717, ed. Cecil Headlam (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1930), 336-344; Bonhams (Auctioneers). Thanks to Klaubernd for his advice on map orientations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.