Category Archives: Shells & Coral Abaco

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS: DECORATIVE CORAL-DWELLERS

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS: DECORATIVE CORAL-DWELLERS

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS Cyphoma gibbous are small marine gastropod molluscs related to cowries. The living animal is brightly coloured and strikingly patterned, but that colour only exists in the ‘live’ parts – the so-called ‘mantle’. The shell itself is usually pale, and characterised by a thick ridge round the middle. Whether alive or as shells, they are gratifyingly easy to identify. These snails live in the tropical waters of the Caribbean and the wider western Atlantic.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CORAL

Flamingo tongue snails feed by browsing on soft corals. Often, they will leave tracks behind them on the coral stems as they forage (see image below). But corals are not only food – they provide the ideal sites for the creature’s breeding cycle.

Adult females attach eggs to coral which they have recently fed upon. About 10 days later, the larvae hatch. They eventually settle onto other gorgonian corals such as Sea Fans. Juveniles tend to live protectively on the underside of coral branches, while adults are far more visible and mobile. Where the snail leaves a feeding scar, the corals can regrow the polyps, and therefore the snail’s feeding preference is generally not harmful to the coral.

The principal purpose of the patterned mantle of tissue over the shell is to act as the creature’s breathing apparatus. The tissue absorbs oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. As it has been (unkindly?) described, the mantle is “basically their lungs, stretched out over their rather boring-looking shell”. There’s more to them than that!

THREATS AND DEFENCE

The species, once common, is becoming rarer. The natural predators include hogfish, pufferfish and spiny lobsters, though the spotted mantle provides some defence by being (a) startling in appearance and (b) on closer inspection by a predator, rather unpalatable. Gorgonian corals contain natural toxins, and instead of secreting these after feeding, the snail stores them. This supplements the defence provided by its APOSEMATIC COLORATION, the vivid colour and /or pattern warning sign to predators found in many animal species.

MANKIND’S CONTRIBUTION

It comes as little surprise to learn that man is considered to be the greatest menace to these little creatures, and the reason for their significant decline in numbers. The threat comes from snorkelers and divers who mistakenly / ignorantly think that the colour of the mantle is the actual shell of the animal, collect up a whole bunch from the reef, and in due course are left with… dead snails and their allegedly dull shells Don’t be a collector; be a protector…

The photos below are of nude flamingo tongue shells. Until I read the ‘boring-looking shell’ comment, I believed everyone thought they were rather lovely… I did, anyway. I still do. You decide!

Image Credits: Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco; Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour; Wiki Leopard

ELKHORN CORAL . REEF LIFE . ABACO . BAHAMAS

ELKHORN CORAL (Acropora palmata) is a widespread reef coral, an unmistakeable species with large branches that resemble elk antlers. The dense growths create an ideal shady habitat for many reef creatures. These include reef fishes of all shapes and sizes, lobsters, shrimps and many more besides. Elkhorn and similar larger corals are essential for the wellbeing both of the reef itself and also its denizens. These creatures in turn benefit the corals and help keep them in a healthy state.

Examples of fish species vital for healthy corals include several types of PARROTFISH, the colourful and voracious herbivores that spend much of their time eating algae off the coral reefs using their beak-like teeth. This algal diet is digested, and the remains excreted as sand. Tread with care on your favourite beach; in part at least, it will consist of parrotfish poop.

Other vital reef species living in the shelter of elkhorn and other corals are the CLEANERS, little fish and shrimps that cater for the wellbeing and grooming of large and even predatory fishes. Gobies, wrasse, Pedersen shrimps and many others pick dead skin and parasites from the ‘client’ fish including their gills, and even from between the teeth of predators. This service is an excellent example of MUTUALISM, a symbiotic relationship in which both parties benefit: close grooming in return for rich pickings of food.

VULNERABILITY TO CLIMATE CRISIS

Formally abundant, over the course of just a couple of decades elkhorn coral (along with all reef life) has been massively affected by climate change. We can all pinpoint the species responsible for much of the habitat decline and destruction, and the primary factors involved. In addition, global changes in weather patterns result in major storms that are rapidly increasing in both frequency and intensity worldwide.

Physical damage to corals may seriously impact on reproductive success: elkhorn coral is no exception. The effects of a reduction of reef fertility are compounded by the fact that natural recovery is in any case inevitably a slow process. The worse the problem gets, the harder it becomes even to survive, let alone recover, let alone increase.

HOW DOES ELKHORN CORAL REPRODUCE?

There are two types of reproduction, which one might call asexual and sexual:

- Elkhorn coral reproduction occurs when a branch breaks off and attaches to the substrate, forming a the start of a new colony. This process is known as Fragmentation and accounts for roughly half of coral spread. Considerable success is being achieved now with many coral species by in effect farming fragments and cloning colonies (see Reef Rescue Network’s coral nurseries)

- Sexual reproduction occurs once a year in August or September, when coral colonies release millions of gametes by Broadcast Spawning

All brilliant photos: Melinda Rogers, with thanks as ever for use permission

‘TELLIN TIME’ – RISE AND SHINE: ABACO SEASHELLS

‘TELLIN TIME’ – RISE AND SHINE: ABACO SEASHELLS

SUNRISE TELLINS Tellina Radiata

These very pretty shells, with their striking pink radials, are sometimes known as ‘rose-petal shells’. They are always tempting to pick up from the sand. The ‘hinges’ (muscles) are very delicate, however, and with many of these shells that wash up on the beach the two halves have separated naturally.

Sunrise tellins are not uncommon, and make good beachcombing trophies They can grow up to about 7 cms / 2.75 inches, and the colouring is very varied, both outside and inside.

TELLIN: THE TRUTH

The occupant of these nice shells is a type of very small clam. They live on the sea-floor, often buried in the sand and with the lid (mostly) shut. When they die (or their shells are bored into by a predator and they are eaten) the shells eventually wash up empty on the beach. There’s not much more to say about them – they perform no tricks and are believed to have vanilla sex lives. Other small clams are quite inventive, doing backflips and copulating with enthusiasm.

Inside Story… not much to tell except (a) very pretty & (b) possible predator bore-hole top right

WHAT ELSE IS THERE TO KNOW ABOUT THEM?

- These clamlets have 5 tiny teeth to chew up their staple diet, mainly plant material

- These include one ‘strong’ tooth and one ‘weak’ one, though it isn’t clear why. How someone found this fact out remains a mystery

- Tellins are native to the Caribbean and north as far as Florida

- They live mainly in quite shallow water, but have been found as deep as 60 foot

- They have no particular rarity value, and are used for marine-based crafting.

TELLIN LAW

You know those lovely tellins you collected during your holiday and took back home to your loved ones? You did take them, didn’t you? You may have committed a crime! In the Bahamas there is no specific prohibition on the removal of tellin shells, certainly not for personal use… but the general rule – law, even – seems to be “in most countries it is illegal to bring back these shells from holidays”.

Linnaean Examples

As ever, the very excellent Bahamas Philatelic Bureau has covered seashells along with all the other wildlife / natural history stamp sets they have produced regularly over the years. The sunrise tellin was featured in 1995. You can find more – much more – on my PHILATELY page.

All photos Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour; Rhonda Pearce, O/S Linnean Poster, O/S BPB stamp

HERMIT CRABS: SHELL-DWELLERS WITH MOBILE HOMES

Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

HERMIT CRABS: SHELL-DWELLERS WITH MOBILE HOMES

As everyone knows, Hermit Crabs get their name from the fact that from an early age they borrow empty seashells to live in. As they grow they trade up to a bigger one, leaving their previous home for a smaller crab to move into. It’s a benign* chain of recycling that the original gastropod occupant would no doubt approve of, were it still alive… The crabs are able to adapt their flexible bodies to their chosen shell. Mostly they are to be found in weathered (‘heritage’) shells rather than newly-empty shells. [*except for fighting over shells]

HERMIT CRAB FACTS TO ENLIVEN YOUR CONVERSATION

- The crabs are mainly terrestrial, and make their homes in empty gastropod shells

- Their bodies are soft, making them vulnerable to predation and heat.

- They are basically naked – the shells protect their bodies & conceal them from predators

- In that way they differ from other crab species that have hard ‘calcified’ shells / carapaces

- Ideally the shell should be the right size to retract into completely, with no bits on display

- As they grow larger, they have to move into larger and larger shells to hide in

- As the video below shows wonderfully, they may form queues and upsize in turns

- Occasionally they make a housing mistake and chose a different home, eg a small tin

Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

- The crabs may congregate in large groups which scatter rapidly when they sense danger

- The demand for suitable shells can be competitive and the cause of inter-crab battles

- Sometimes two or more will gang up on a rival to prevent its move to a particular shell

HERMIT CRABS CAN EVEN CLIMB TREES – WITH THEIR SHELLS ON TOO

Tom Sheley

HERMIT CRABS EXCHANGING HOMES with DAVID ATTENBOROUGH

This is a short (c 4 mins) extract from BBC Earth, with David Attenborough explaining about the lives and habits of these little crabs with his usual authoritative care and precision . If you have the time I highly recommend taking a look.

Credits: All photos taken on Abaco by Keith Salvesen except for the tree-climber crab photographed by Tom Sheley; video from BBC Earth

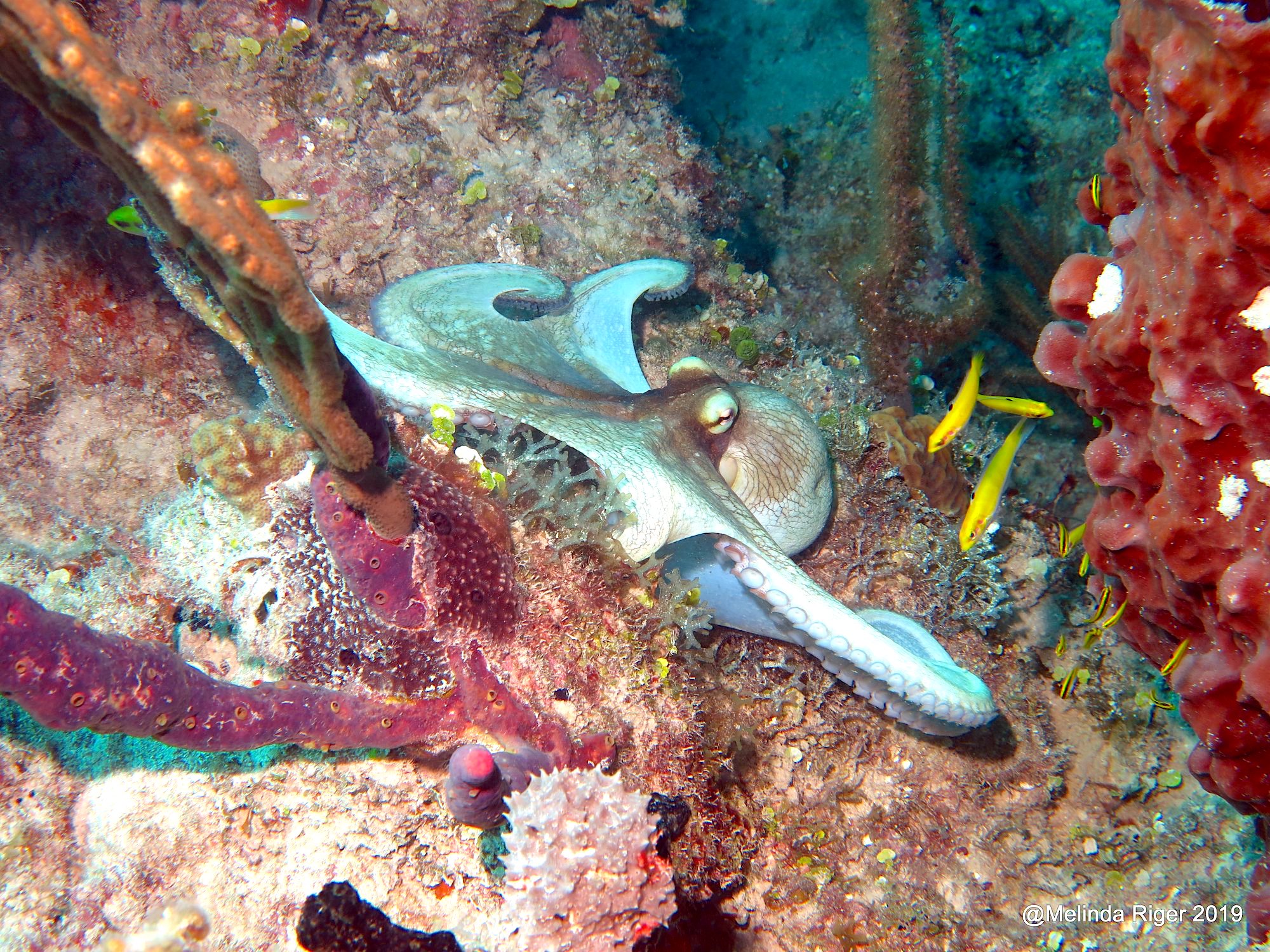

OCTOPUS’S GARDEN (TAKE 9) IN THE BAHAMAS

OCTOPUS’S GARDEN (TAKE 9) IN THE BAHAMAS

We are back again under the sea, warm below the storm, with an eight-limbed companion in its little hideaway beneath the waves.

It’s impossible to imagine anyone failing to engage with these extraordinary, intelligent creatures as they move around the reef. Except for octopodophobes, I suppose. I’ve written about octopuses quite a lot, yet each time I get to look at a new batch of images, I feel strangely elated that such a intricate, complex animal can exist.

While examining the photo above, I took a closer look bottom left at the small dark shape. Yes my friends, it is (as you feared) a squished-looking seahorse,

The kind of image a Scottish bagpiper should avoid seeing n

n

OPTIONAL MUSICAL DIGRESSION

With octopus posts I sometimes (rather cornily, I know) feature the Beatles’ great tribute to the species, as voiced with a delicacy and tunefulness that only Ringo was capable of. There’s some fun to be had from the multi-bonus-track retreads currently so popular. These ‘extra features’ include alternative mixes, live versions and – most egregious of all except for the most committed – ‘Takes’. These are the musical equivalent of a Picasso drawing that he botched or spilt his wine over and chucked in the bin, from which his agent faithfully rescued it (it’s now in MOMA…)

You might enjoy OG Take 9, though, for the chit chat and Ringo’s endearingly off-key moments.

All fabulous photos by Melinda Riger, Grand Bahama Scuba taken a few days ago

URCHIN RESEARCHIN’: SEA HEDGEHOGS OF THE REEF

URCHIN RESEARCHIN’: SEA HEDGEHOGS OF THE REEF

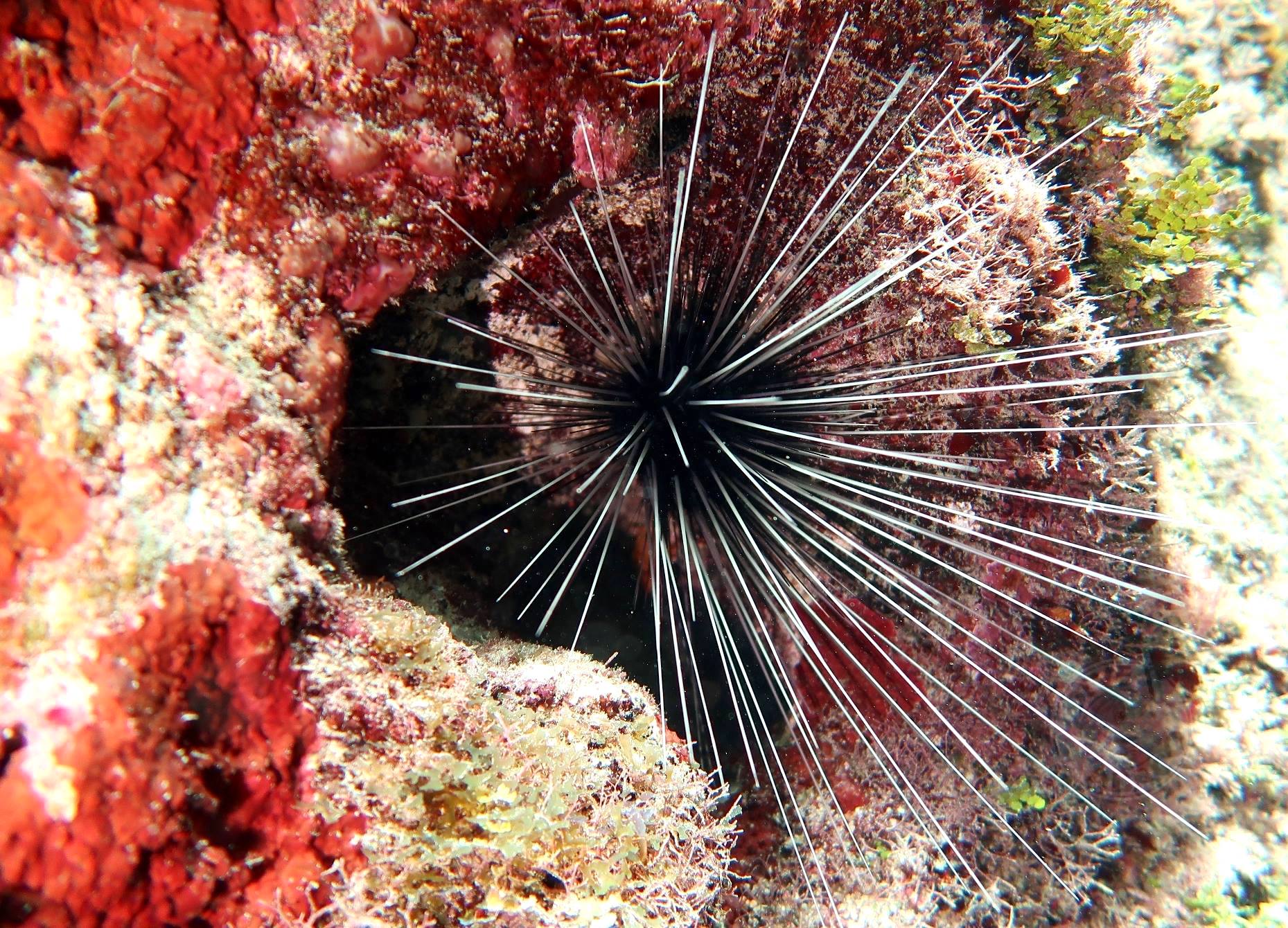

The long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum featured in this post is one of those creatures that handily offers its USP in its name, so you know what you are dealing with. Something prickly, for a start. These are creatures of the reef, and many places in the Caribbean and in the western Atlantic generally sustain healthy populations.

These animals are essentially herbivores, and their value to vulnerable coral reefs cannot be overstated. Where there is a healthy population of these urchins, the reef will be kept clean from smothering algae by their methodical grazing. They also eat sea grass.

HOW DO THE SPINES OF DIFFERENT KINDS OF URCHIN COMPARE?

CAN YOU GIVE US A TEST, PLEASE?

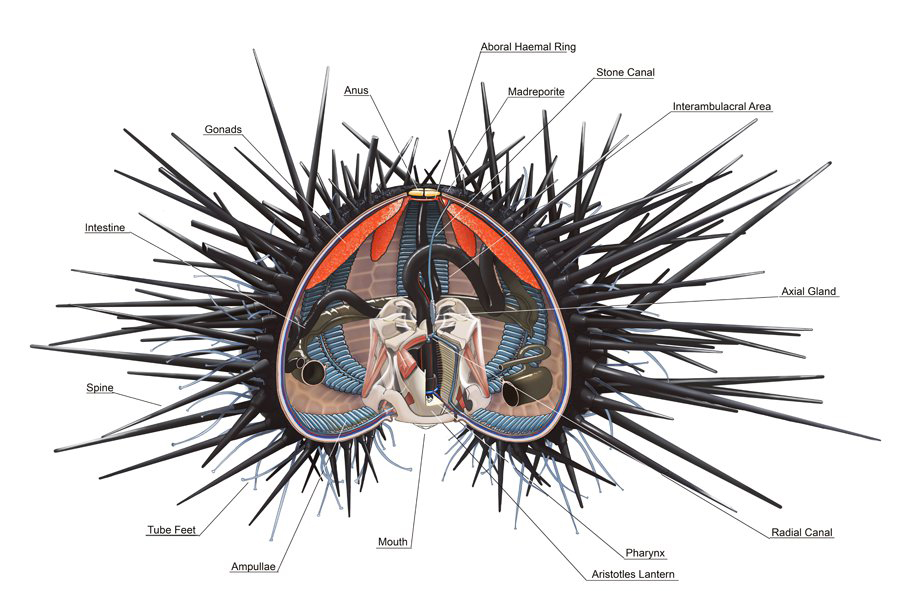

A BIT ABOUT SYMMETRY

Sea urchins are born with bilateral symmetry – in effect, you could fold one in half. If you wear gloves. As they grow to adulthood, they retain symmetry but develop so-called ‘fivefold symmetry’, rather as if an orange contained 5 equal-sized segments. The graphic above gives a good idea of how the interior is arranged inside the segments.

A FEW FACTS TO HAND DOWN TO YOUR CHILDREN

- Urchin fossil records date the species back to the Ordivician period c 40m years ago

- In the ’90s the population was decimated and still has not recovered fully

- Urchins feel stress: a bad sign that the spines here are white rather than black

- Urchins are not only warm water creatures: some kinds live in polar regions

- Urchins are of particular use in scientific research, including genome studies

- Some urchins end up in aquariums / aquaria, where I doubt the algae is so tasty

- Kindest not to prod or tread on them

- Their nearest relative (surprisingly) is said to be the Sea Cucumber

ARE THEY EDIBLE?

They are eaten in some parts of the world, but only where the gonads and roe are considered a delicacy. Personally, I could leave them or leave them.

CREDITS: Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco (1, 2, 3, 6, 9) taken Abaco; Melinda Riger / G B Scuba (4, 10, 11) taken Grand Bahama; Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour (7, 8) taken Abaco; Wiki graphic (5) CC . RESEARCH Fred Riger for detailed information; otherwise magpie pickings… This is an archive post

BRAIN WAVES: UNDERSEA CORAL MAZES & LABYRINTHS

BRAIN WAVES: UNDERSEA CORAL MAZES & LABYRINTHS

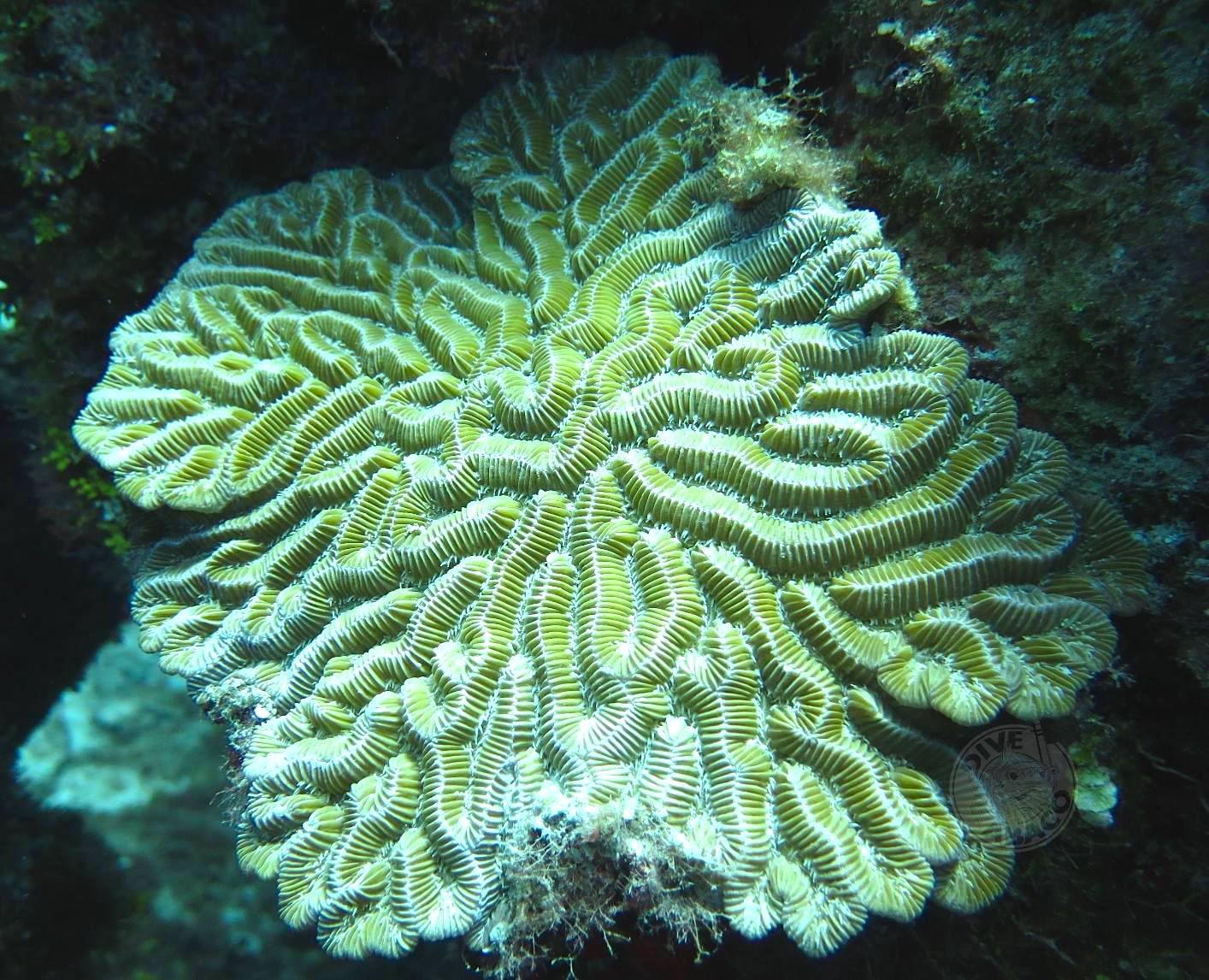

The most apposite description of brain coral Diploria labyrinthiformisis is essentially a no-brainer. How could you not call the creatures on this page anything else**. These corals come in wide varieties of shape and colour, and 4 types are found in Caribbean waters. They date from the Jurassic period.

Each ‘brain’ is in fact a complex colony consisting of genetically similar polyps. These secrete CALCIUM CARBONATE which forms a hard carapace. This chemical compound is found in minerals, the shells of sea creatures, eggs, and even pearls. In human terms it has many industrial applications and widespread medicinal use, most familiarly in the treatment of gastric problems.

The hardness of this type of coral makes it an important component of reefs throughout warm water zones world-wide. The dense protection also guarantees (or did until our generation began systematically to dismantle the earth) – extraordinary longevity. The largest brain corals develop to a height of almost 2 meters, and are believed to be several hundred years old.

HOW ON EARTH DO THEY LIVE?

If you look closely at the cropped image below and other images on this page, you will see thousands of tiny tentacles nestled in the trenches on the surface. These corals feed at night, deploying their tentacles to catch food. Their diet consists of tiny creatures and their algal contents. During the day, the tentacles retract into the sinuous grooves. Some brain corals have developed tentacles with defensive stings.

THE TRACKS LOOKS LIKE MAZES OR DO I MEAN LABYRINTHS?

The difference between mazes and labyrinths is that labyrinths have a single continuous path which leads to the centre. As long as you keep going forward, you will get there eventually. You can’t get lost. Mazes have multiple paths which branch off and will not necessarily lead to the centre. There are dead ends. Therefore, you can get lost. Or never get to the centre at all.

** On the corals shown here, you will get lost in blind alleys almost at once. Therefore in human terms these are mazes. The taxonomic labyrinthiformisis is Latin derived from Greek, and applied generally to this kind of structure, whether in actual fact a labyrinth or a maze.

CREDIT: all amazing underwater brain-work thanks to Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco; Lucca Labyrinth, Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

Here is a beautiful inscribed labyrinth dating from c12 or c13 from the porch of St Martin’s Cathedral in Lucca, Italy. Very beautiful but not such a challenge.

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS: DECORATIVE CORAL-DWELLERS

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS: DECORATIVE CORAL-DWELLERS

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS Cyphoma gibbous are small marine gastropod molluscs related to cowries. The living animal is brightly coloured and strikingly patterned, but that colour only exists in the ‘live’ parts – the so-called ‘mantle’. The shell itself is usually pale, and characterised by a thick ridge round the middle. Whether alive or as shells, they are gratifyingly easy to identify. These snails live in the tropical waters of the Caribbean and the wider western Atlantic.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CORAL

Flamingo tongue snails feed by browsing on soft corals. Often, they will leave tracks behind them on the coral stems as they forage (see image below). But corals are not only food – they provide the ideal sites for the creature’s breeding cycle.

Adult females attach eggs to coral which they have recently fed upon. About 10 days later, the larvae hatch. They eventually settle onto other gorgonian corals such as Sea Fans. Juveniles tend to live protectively on the underside of coral branches, while adults are far more visible and mobile. Where the snail leaves a feeding scar, the corals can regrow the polyps, and therefore the snail’s feeding preference is generally not harmful to the coral.

The principal purpose of the patterned mantle of tissue over the shell is to act as the creature’s breathing apparatus. The tissue absorbs oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. As it has been (unkindly?) described, the mantle is “basically their lungs, stretched out over their rather boring-looking shell”. There’s more to them than that!

THREATS AND DEFENCE

The species, once common, is becoming rarer. The natural predators include hogfish, pufferfish and spiny lobsters, though the spotted mantle provides some defence by being (a) startling in appearance and (b) on closer inspection by a predator, rather unpalatable. Gorgonian corals contain natural toxins, and instead of secreting these after feeding, the snail stores them. This supplements the defence provided by its APOSEMATIC COLORATION, the vivid colour and /or pattern warning sign to predators found in many animal species.

MANKIND’S CONTRIBUTION

It comes as little surprise to learn that man is considered to be the greatest menace to these little creatures, and the reason for their significant decline in numbers. The threat comes from snorkelers and divers who mistakenly / ignorantly think that the colour of the mantle is the actual shell of the animal, collect up a whole bunch from the reef, and in due course are left with… dead snails and their allegedly dull shells Don’t be a collector; be a protector…

The photos below are of nude flamingo tongue shells. Until I read the ‘boring-looking shell’ comment, I believed everyone thought they were rather lovely… I did, anyway. I still do. You decide!

Image Credits: Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco; Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour; Wiki Leopard

TUNICATES: SESSILE ASEXUAL SEA-SQUIRTS

TUNICATES: SESSILE ASEXUAL SEA-SQUIRTS

Painted Tunicates Clavina picta are one of several species of tunicate ‘sea-squirts’ found in Bahamas and Caribbean waters. These creatures with their translucent bodies are usually found clustered together, sometimes in very large groups. One reason for this is that they are ‘sessile’, unable to move from where they have taken root on the coral.

HOW DO THEY FEED?

Like most if not all sea squirts, tunicates are filter feeders. Their structure is simple, and enables them to draw water into their body cavity. In fact they have 2 openings, an ‘oral siphon’ to suck in water; and an exit called the ‘atrial siphon’. Tiny particles of food (e.g. plankton) are separated internally from the water by means of a tiny organ (‘branchial basket’) like a sieve. The water is then expelled.

WHAT DOES ‘TUNICATE’ MEAN?

The creatures have a flexible protective covering referred to as a ‘tunic’. ‘Coveringcates’ didn’t really work as a name, so the tunic aspect became the name.

IF THEY CAN’T MOVE, HOW DO THEY… (erm…) REPRODUCE?

Tunicates are broadly speaking asexual. Once a colony has become attached to corals or sponges, they are able to ‘bud’, ie to produce clones to join the colony. These are like tiny tadpoles and their first task is to settle and attach themselves to something suitable – for life – using a sticky secretion. Apparently they do this head first, then in effect turn themselves upside down as they develop the internal bits and pieces they need for adult life. The colony grows because (*speculation alert*) the most obvious place for the ‘tadpoles’ to take root is presumably in the immediate area they were formed.

APART FROM BEING STATIONARY & ASEXUAL, ANY OTHER ATTRIBUTES?

Some types of tunicate contain particular chemicals that are related to those used to combat some forms of cancer and a number of viruses. So they have a potential use in medical treatments, in particular in helping to repair tissue damage.

BRAIN WAVES: UNDERSEA CORAL MAZES & LABYRINTHS

BRAIN WAVES: UNDERSEA CORAL MAZES & LABYRINTHS

The most apposite description of brain coral Diploria labyrinthiformisis is essentially a no-brainer. How could you not call the creatures on this page anything else**. These corals come in wide varieties of shape and colour, and 4 types are found in Caribbean waters. They date from the Jurassic period.

Each ‘brain’ is in fact a complex colony consisting of genetically similar polyps. These secrete CALCIUM CARBONATE which forms a hard carapace. This chemical compound is found in minerals, the shells of sea creatures, eggs, and even pearls. In human terms it has many industrial applications and widespread medicinal use, most familiarly in the treatment of gastric problems.

The hardness of this type of coral makes it an important component of reefs throughout warm water zones world-wide. The dense protection also guarantees (or did until our generation began systematically to dismantle the earth) – extraordinary longevity. The largest brain corals develop to a height of almost 2 meters, and are believed to be several hundred years old.

HOW ON EARTH DO THEY LIVE?

If you look closely at the cropped image below and other images on this page, you will see thousands of tiny tentacles nestled in the trenches on the surface. These corals feed at night, deploying their tentacles to catch food. Their diet consists of tiny creatures and their algal contents. During the day, the tentacles retract into the sinuous grooves. Some brain corals have developed tentacles with defensive stings.

THE TRACKS LOOKS LIKE MAZES OR DO I MEAN LABYRINTHS?

The difference between mazes and labyrinths is that labyrinths have a single continuous path which leads to the centre. As long as you keep going forward, you will get there eventually. You can’t get lost. Mazes have multiple paths which branch off and will not necessarily lead to the centre. There are dead ends. Therefore, you can get lost. Or never get to the centre at all.

** On the corals shown here, you will get lost in blind alleys almost at once. Therefore in human terms these are mazes. The taxonomic labyrinthiformisis is Latin derived from Greek, and applied generally to this kind of structure, whether in actual fact a labyrinth or a maze.

CREDIT: all amazing underwater brain-work thanks to Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco; Lucca Labyrinth, Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

Here is a beautiful inscribed labyrinth dating from c12 or c13 from the porch of St Martin’s Cathedral in Lucca, Italy. Very beautiful but not such a challenge.

ELKHORN CORAL – REEF LIFE . ABACO . BAHAMAS

ELKHORN CORAL (Acropora palmata) is a widespread reef coral, an unmistakeable species with large branches that resemble elk antlers. The dense growths create an ideal shady habitat for many reef creatures. These include reef fishes of all shapes and sizes, lobsters, shrimps and many more besides. Elkhorn and similar larger corals are essential for the wellbeing both of the reef itself and also its denizens. These creatures in turn benefit the corals and help keep them in a healthy state.

Examples of fish species vital for healthy corals include several types of PARROTFISH, the colourful and voracious herbivores that spend much of their time eating algae off the coral reefs using their beak-like teeth. This algal diet is digested, and the remains excreted as sand. Tread with care on your favourite beach; in part at least, it will consist of parrotfish poop.

Other vital reef species living in the shelter of elkhorn and other corals are the CLEANERS, little fish and shrimps that cater for the wellbeing and grooming of large and even predatory fishes. Gobies, wrasse, Pedersen shrimps and many others pick dead skin and parasites from the ‘client’ fish including their gills, and even from between the teeth of predators. This service is an excellent example of MUTUALISM, a symbiotic relationship in which both parties benefit: close grooming in return for rich pickings of food.

VULNERABILITY TO CLIMATE CRISIS

Formally abundant, over the course of just a couple of decades elkhorn coral (along with all reef life) has been massively affected by climate change. We can all pinpoint the species responsible for much of the habitat decline and destruction, and the primary factors involved. In addition, global changes in weather patterns result in major storms that are rapidly increasing in both frequency and intensity worldwide.

Physical damage to corals may seriously impact on reproductive success: elkhorn coral is no exception. The effects of a reduction of reef fertility are compounded by the fact that natural recovery is in any case inevitably a slow process. The worse the problem gets, the harder it becomes even to survive, let alone recover, let alone increase.

HOW DOES ELKHORN CORAL REPRODUCE?

There are two types of reproduction, which one might call asexual and sexual:

- Elkhorn coral reproduction occurs when a branch breaks off and attaches to the substrate, forming a the start of a new colony. This process is known as Fragmentation and accounts for roughly half of coral spread. Considerable success is being achieved now with many coral species by in effect farming fragments and cloning colonies (see Reef Rescue Network’s coral nurseries)

- Sexual reproduction occurs once a year in August or September, when coral colonies release millions of gametes by Broadcast Spawning

All photos: Melinda Rogers, with thanks as ever for use permission

HERMIT CRABS: SHELL-DWELLERS WITH MOBILE HOMES

HERMIT CRABS: SHELL-DWELLERS WITH MOBILE HOMES

As everyone knows, Hermit Crabs get their name from the fact that from an early age they borrow empty seashells to live in. As they grow they trade up to a bigger one, leaving their previous home for a smaller crab to move into. It’s a benign** chain of recycling that the original gastropod occupant would no doubt approve of, were it still alive… The crabs are able to adapt their flexible bodies to their chosen shell. Mostly they are to be found in weathered (‘heritage’) rather than newly-empty shells for their home. [**except for fighting over shells]

HERMIT CRAB FACTS TO ENLIVEN YOUR CONVERSATION

- The crabs are mainly terrestrial, and make their homes in empty gastropod shells

- Their bodies are soft, making them vulnerable to predation and heat.

- They are basically naked – the shells protect their bodies & conceal them from predators

- In that way they differ from other crab species that have hard ‘calcified’ shells / carapaces

- Ideally the shell should be the right size to retract into completely, with no bits on display

- As they grow larger, they have to move into larger and larger shells to hide in

- As the video below shows wonderfully, they may form queues and upsize in turns

- Occasionally they make a housing mistake and chose a different home, eg a small tin

- The crabs may congregate in large groups which scatter rapidly when they sense danger

- The demand for suitable shells can be competitive and the cause of inter-crab battles

- Sometimes two or more will gang up on a rival to prevent its move to a particular shell

HERMIT CRABS CAN EVEN CLIMB TREES – WITH THEIR SHELLS ON TOO

HERMIT CRABS EXCHANGING HOMES with DAVID ATTENBOROUGH

This is a short (c 4 mins) extract from BBC Earth, with David Attenborough explaining about the lives and habits of these little crabs with his usual authoritative care and precision . If you have the time I highly recommend taking a look.

Credits: All photos taken on Abaco by Keith Salvesen except for the tree-climber crab photographed by Tom Sheley; video from BBC Earth

‘TELLIN TIME’ – RISE AND SHINE: ABACO SEASHELLS

‘TELLIN TIME’ – RISE AND SHINE: ABACO SEASHELLS

SUNRISE TELLINS Tellina Radiata

These very pretty shells, with their striking pink radials, are sometimes known as ‘rose-petal shells’. They are always tempting to pick up from the sand. The ‘hinges’ (muscles) are very delicate, however, and with many of these shells that wash up on the beach the two halves have separated naturally.

Sunrise tellins are not uncommon, and make good beachcombing trophies They can grow up to about 7 cms / 2.75 inches, and the colouring is very varied, both outside and inside.

TELLIN: THE TRUTH

The occupant of these nice shells is a type of very small clam. They live on the sea-floor, often buried in the sand and with the lid (mostly) shut. When they die (or their shells are bored into by a predator and they are eaten) the shells eventually wash up empty on the beach. There’s not much more to say about them – they perform no tricks and are believed to have vanilla sex lives. Other small clams are quite inventive, doing backflips and copulating with enthusiasm.

Inside Story… not much to tell except (a) very pretty & (b) possible predator bore-hole top right

WHAT ELSE IS THERE TO KNOW ABOUT THEM?

- These clamlets have 5 tiny teeth to chew up their staple diet, mainly plant material

- These include one ‘strong’ tooth and one ‘weak’ one, though it isn’t clear why. How someone found this fact out remains a mystery

- Tellins are native to the Caribbean and north as far as Florida

- They live mainly in quite shallow water, but have been found as deep as 60 foot

- They have no particular rarity value, and are used for marine-based crafting.

TELLIN LAW

You know those lovely tellins you collected during your holiday and took back home to your loved ones? You did take them, didn’t you? You may have committed a crime! In the Bahamas there is no specific prohibition on the removal of tellin shells, certainly not for personal use… but the general rule – law, even – seems to be “in most countries it is illegal to bring back these shells from holidays”.

Linnaean Examples

As ever, the very excellent Bahamas Philatelic Bureau has covered seashells along with all the other wildlife / natural history stamp sets they have produced regularly over the years. The sunrise tellin was featured in 1995. You can find more – much more – on my PHILATELY page.

All photos Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour; Rhonda Pearce, O/S Linnean Poster, O/S BPB stamp

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS: DECORATIVE CORAL-DWELLERS

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS: DECORATIVE CORAL-DWELLERS

FLAMINGO TONGUE SNAILS Cyphoma gibbous are small marine gastropod molluscs related to cowries. The living animal is brightly coloured and strikingly patterned, but that colour only exists in the ‘live’ parts – the so-called ‘mantle’. The shell itself is usually pale, and characterised by a thick ridge round the middle. These snails live in the tropical waters of the Caribbean and the wider western Atlantic. Whether alive or dead, they are gratifyingly easy to identify.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CORAL

Flamingo tongue snails feed by browsing on soft corals. Often, they will leave tracks behind them on the coral stems as they forage (see image below). But corals are not only food – they provide the ideal sites for the creature’s breeding cycle.

Adult females attach eggs to coral which they have recently fed upon. About 10 days later, the larvae hatch. They eventually settle onto other gorgonian corals such as Sea Fans. Juveniles tend to live on the underside of coral branches, while adults are far more visible and mobile. Where the snail leaves a feeding scar, the corals can regrow the polyps, and therefore the snail’s feeding preference is generally not harmful to the coral.

The principal purpose of the patterned mantle of tissue over the shell is to act as the creature’s breathing apparatus. The tissue absorbs oxygen and releases carbon dioxide. As it has been (unkindly?) described, the mantle is “basically their lungs, stretched out over their rather boring-looking shell”.

THREATS AND DEFENCE

The species, once common, is becoming rarer. The natural predators include hogfish, pufferfish and spiny lobsters, though the spotted mantle provides some defence by being rather unpalatable. Gorgonian corals contain natural toxins, and instead of secreting these after feeding, the snail stores them. This supplements the defence provided by its APOSEMATIC COLORATION, the vivid colour and /or pattern warning sign to predators found in many animal species.

MANKIND’S CONTRIBUTION

It comes as little surprise to learn that man is now considered to be the greatest menace to these little creatures, and the reason for their significant decline in numbers. The threat comes from snorkelers and divers who mistakenly / ignorantly think that the colour of the mantle is the actual shell of the animal, collect up a whole bunch from the reef, and in due course are left with… dead snails and “boring-looking shells” (see photos below). Don’t be a collector; be a protector…

The photos below are of nude flamingo tongue shells from the Delphi Club Collection. Until I read the ‘boring-looking shell’ comment, I believed everyone thought they were rather lovely… I did, anyway. You decide!

Image Credits: Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco; Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

TUNICATES: SESSILE ASEXUAL SEA-SQUIRTS

TUNICATES: SESSILE ASEXUAL SEA-SQUIRTS

Painted Tunicates Clavina picta are one of several species of tunicate ‘sea-squirts’ found in Bahamas and Caribbean waters. These creatures with their translucent bodies are usually found clustered together, sometimes in very large groups. One reason for this is that they are ‘sessile’, unable to move from where they have taken root on the coral.

HOW DO THEY FEED?

Like most if not all sea squirts, tunicates are filter feeders. Their structure is simple, and enables them to draw water into their body cavity. In fact they have 2 openings, an ‘oral siphon’ to suck in water; and an exit called the ‘atrial siphon’. Tiny particles of food (e.g. plankton) are separated internally from the water by means of a tiny organ (‘branchial basket’) like a sieve. The water is then expelled.

WHAT DOES ‘TUNICATE’ MEAN?

The creatures have a flexible protective covering referred to as a ‘tunic’. ‘Coveringcates’ didn’t really work as a name, so the tunic aspect became the name.

IF THEY CAN’T MOVE, HOW DO THEY… (erm…) REPRODUCE?

Tunicates are broadly speaking asexual. Once a colony has become attached to corals or sponges, they are able to ‘bud’, ie to produce clones to join the colony. These are like tiny tadpoles and their first task is to settle and attach themselves to something suitable – for life – using a sticky secretion. Apparently they do this head first, then in effect turn themselves upside down as they develop the internal bits and pieces they need for adult life. The colony grows because (*speculation alert*) the most obvious place for the ‘tadpoles’ to take root is presumably in the immediate area they were formed.

APART FROM BEING STATIONARY & ASEXUAL, ANY OTHER ATTRIBUTES?

Some types of tunicate contain particular chemicals that are related to those used to combat some forms of cancer and a number of viruses. So they have a potential use in medical treatments, in particular in helping to repair tissue damage.

OCTOPUS’S GARDEN (TAKE 9) IN THE BAHAMAS

OCTOPUS’S GARDEN (TAKE 9) IN THE BAHAMAS

We are back again under the sea, warm below the storm, with an eight-limbed companion in its little hideaway beneath the waves.

It’s impossible to imagine anyone failing to engage with these extraordinary, intelligent creatures as they move around the reef. Except for octopodophobes, I suppose. I’ve written about octopuses quite a lot, yet each time I get to look at a new batch of images, I feel strangely elated that such a intricate, complex animal can exist.

While examining the photo above, I took a closer look bottom left at the small dark shape. Yes my friends, it is (as you feared) a squished-looking seahorse,

The kind of image a Scottish bagpiper should avoid seeing

The kind of image a Scottish bagpiper should avoid seeing

OPTIONAL MUSICAL DIGRESSION

OPTIONAL MUSICAL DIGRESSION

With octopus posts I sometimes (rather cornily, I know) feature the Beatles’ great tribute to the species, as voiced with a delicacy that only Ringo was capable of. There’s some fun to be had from the multi-bonus-track retreads currently so popular. These ‘extra features’ include alternative mixes, live versions and – most egregious of all except for the most committed – ‘Takes’. These are the musical equivalent of a Picasso drawing that he botched or spilt his wine over and chucked in the bin, from which his agent faithfully rescued it (it’s now in MOMA…)

You might enjoy OG Take 9, though, for the chit chat and Ringo’s endearingly off-key moments.

All fabulous photos by Melinda Riger, Grand Bahama Scuba taken a few days ago

BRAIN WAVES: UNDERSEA CORAL MAZES & LABYRINTHS

BRAIN WAVES: UNDERSEA CORAL MAZES & LABYRINTHS

The name ‘brain coral’ is essentially a no-brainer. How could you not call the creatures on this page anything else. These corals come in wide varieties of colour, shape and – well, braininess – and are divided into two main families worldwide.

Each ‘brain’ is in fact a complex colony consisting of genetically similar polyps. These secrete CALCIUM CARBONATE which forms a hard carapace. This chemical compound is found in minerals, the shells of sea creatures, eggs, and even pearls. In human terms it has many industrial applications and widespread medicinal use, most familiarly in the treatment of gastric problems.

The hardness of this type of coral makes it a important component of reefs throughout warm water zones world-wide. The dense protection also guarantees (or did until our generation began systematically to dismantle the earth) – extraordinary longevity. The largest brain corals develop to a height of almost 2 meters, and are believed to be several hundred years old.

HOW ON EARTH DO THEY LIVE?

If you look closely at the cropped image below and other images on this page, you will see hundreds of little tentacles nestled in the trenches on the surface. These corals feed at night, deploying their tentacles to catch food. This consists of tiny creatures and their algal contents. During the day, the tentacles are retracted into the sinuous grooves. Some brain corals have developed tentacles with defensive stings.

THE TRACKS LOOKS LIKE MAZES OR DO I MEAN LABYRINTHS?

Mazes, I think. The difference between mazes and labyrinths is that labyrinths have a single continuous path which leads to the centre. As long as you keep going forward, you will get there eventually. You can’t get lost. Mazes have multiple paths which branch off and will not necessarily lead to the centre. There are dead ends. Therefore, you can get lost. Check out which type of puzzle occurs on brain coral. Answer below…**

CREDIT: all amazing underwater brain-work thanks to Melinda Rogers / Dive Abaco; Lucca Labyrinth, Keith Salvesen / Rolling Harbour

** On the coral I got lost straight away in blind alleys. Therefore these are mazes. Here is a beautiful inscribed labyrinth dating from c12 or c13 from the porch of St Martin Cathedral in Lucca, Italy. Very beautiful but not such a challenge.

ELKHORN CORAL, ABACO BAHAMAS (DORIAN UPDATE)

ELKHORN CORAL, ABACO BAHAMAS (DORIAN UPDATE)

Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) is a widespread reef coral, an unmistakeable species with large branches that resemble elk antlers. The dense growths create an ideal shady habitat for many reef creatures. These include reef fishes of all shapes and sizes, lobsters, shrimps and many more besides. Some of these are essential for the wellbeing of the reef and also its denizens.

GOOD POST-DORIAN NEWS ABOUT ABACORAL

A recent report from FRIENDS OF THE ENVIRONMENT brings encouraging news about the reefs of Abaco post-hurricane, and an indication of the resilience of the coral to extreme conditions (with one exception for a reef too close to the shore to avoid damage from debris).

Shortly before Dorian hit, The Perry Institute for Marine Science and its partners surveyed reefs across Grand Bahama and Abaco to assess their health. Following Dorian, they were able to reassess these areas and the impact of the hurricane. Over the 370 miles that the surveys covered, minimal damage was found on the majority of reefs. Unfortunately Mermaid Reef, where FRIENDS does most of our educational field trips, sustained extensive damage due to debris from its close proximity to the shoreline. We are looking into how we can help with logistics to get the debris removed, and hopefully the recovery will begin soon.

The scientists were also able to visit four of the Reef Rescue Network’s coral nurseries and assess out-planted corals in national parks in both Grand Bahama and Abaco. The great news is that all of the corals on these nurseries survived the storm and will be used to support reef restoration. Also from the surveys, it appears that our offshore reefs around Abaco sustained minimal damage, including Sandy Cay Reef in Pelican Cays Land and Sea Park (pictured above). This gives us hope for the recovery of our oceans post-Dorian and proves how resilient these amazing ecosystems are.

Examples of species vital for healthy corals include several types of PARROTFISH, the colourful and voracious herbivores that spend most of their time eating algae off the coral reefs using their beak-like teeth. This algal diet is digested, and the remains excreted as sand. Tread with care on your favourite beach; in part at least, it will consist of parrotfish poop.

Other vital reef species living in the shelter of elkhorn and other corals are the CLEANERS, little fish and shrimps that cater for the wellbeing and grooming of large and even predatory fishes. Gobies, wrasse, Pedersen shrimps and many others pick dead skin and parasites from the ‘client’ fish including their gills, and even from between the teeth of predators. This service is an excellent example of MUTUALISM, a symbiotic relationship in which both parties benefit: close grooming in return for rich pickings of food.

VULNERABILITY TO OFFICIALLY NON-EXISTENT CLIMATE CRISIS

Formally abundant, over just a couple of decades elkhorn coral has been massively affected by [climate change, human activity and habitat destruction] inexplicable natural attrition in many areas. One cause of decline that is incontrovertible is damage from storms, which are empirically increasing in both frequency and intensity, though apparently for no known reason.

Physical damage to corals may seriously impact on reproductive success; elkhorn coral is no exception. The effects of a reduction of reef fertility are compounded by the fact that natural recovery is in any case inevitably a slow process. The worse the problem gets, the harder it becomes even to survive let alone recover.

SO HOW DOES ELKHORN CORAL REPRODUCE?

There are two types of reproduction, which one might call asexual and sexual:

- Elkhorn coral reproduction occurs when a branch breaks off and attaches to the substrate, forming a the start of a new colony. This process is known as fragmentation and accounts for roughly half of coral spread. Considerable success is being achieved now with many coral species by in effect farming fragments and cloning colonies (see above, Reef Rescue Network’s coral nurseries)

- Sexual reproduction occurs once a year in August or September, when coral colonies release millions of gametes by broadcast spawning (there’s much more to be said on this interesting topic, and one day I will)

THE FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHS

You may have wondered in which healthily coral-infested waters these superb elkhorn coral photographs were taken. Did I perhaps source them from a National Geographic coral reef special edition? In fact, every image featured was obtained among the reefs of Abaco.

All except the recent Perry Institute / Friends of the Environment photo were taken by Melinda Rogers of Dive Abaco, Marsh Harbour. The long-established and highly regarded Dive Shop she and her husband Keith run was obliterated (see above) less than 3 months ago by Hurricane Dorian, along with most of the rest of the town. It’s a pleasure to be able to showcase these images taken in sunnier times.

AN OCTOPUS’S GARDEN, BAHAMAS

AN OCTOPUS’S GARDEN, BAHAMAS

Many of us, from time to time, might like to be under the sea, warm below the storm, swimming about the coral that lies beneath the ocean waves. Though possibly not resting their heads on the seabed. This undeniably idyllic experience would be perfected by the presence of an octopus and the notional garden he lives in. Enough to make any person shout and swim about – and quite excessively at that.

The extra ingredient here is that these photographs were taken on the reef off the southern coast of Grand Bahama last week, less than 2 months after the island (along with Abaco) was smashed up by Hurricane Dorian. Thankfully, Grand Bahama Scuba has been able to return to relative normality and run diving trips again. Moreover, fears for the reefs have proved relatively unfounded. These images suggest little damage from the massive storm. The Abaco reefs have not yet been able to be assessed in any detail.

The feature creature here was observed and photographed as it took it a octopodic wander round the reef. The vivid small fishes are out and about. The reef and its static (technically ‘sessile’) life forms – corals, anemones and sponges – look in good order. The octopus takes a pause to assess its surroundings before moving on to another part of the reef.

THE PLURAL(S) OF OCTOPUS REVISITED

A long time ago I wrote a quasi-learned disquisition on the correct plural for the octopus. There were at least 3 possibilities derived from Greek and Latin, all arguable but none so sensible or normal-sounding as ‘octopuses‘. The other 2 are octopi and octopodes. If you want the bother with the details check out THE PLURAL OF OCTOPUS.

There’s an aspect I missed then, through rank ignorance I’d say: I didn’t check the details of the Scientific Classification. Now that I am more ‘Linnaeus-woke’, I have two further plural candidates with impeccable credentials. Octopuses are cephalpods (‘headfeet’) of the Order Octopoda and the Family Octopodidae. These names have existed since naturalist GEORGES CUVIER (he of the beaked whale found in Bahamas waters) classified them thus in 1797.

There’s an aspect I missed then, through rank ignorance I’d say: I didn’t check the details of the Scientific Classification. Now that I am more ‘Linnaeus-woke’, I have two further plural candidates with impeccable credentials. Octopuses are cephalpods (‘headfeet’) of the Order Octopoda and the Family Octopodidae. These names have existed since naturalist GEORGES CUVIER (he of the beaked whale found in Bahamas waters) classified them thus in 1797.

RH ADVICE stick with ‘octopuses’ and (a) you won’t be wrong (b) you won’t get into an un-winnable argument with a pedant and (3) you won’t sound pretentious

OPTIONAL MUSICAL DIGRESSION

Whether you are 9 or 90, you can never have too much of this one. If you are somewhere in the middle – or having Ringo Starr free-styling vocals doesn’t appeal – you can. Step back from the vid.

All fabulous photos by Melinda Riger, Grand Bahama Scuba, Nov 2019

You must be logged in to post a comment.